The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Strange Adventures of Eric Blackburn, by

Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Strange Adventures of Eric Blackburn

Author: Harry Collingwood

Illustrator: C.M. Padday, R.O.I.

Release Date: April 13, 2007 [EBook #21058]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ADVENTURES OF ERIC BLACKBURN ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"The Strange Adventures of Eric Blackburn"

Chapter One.

The Catastrophe.

It happened on our seventh night out from Cape Town, when we had accomplished about a third of the distance between that city and Melbourne.

The ship was the Saturn, of the well-known Planet Line of combined freight and passenger steamers trading between London, Cape Town, and Melbourne; and I—Eric Blackburn, aged a trifle over twenty-three years—was her fourth officer.

The Saturn was a brand-new ship, this being her maiden voyage. She was a twin-screw, of 9800 tons register, 100 A1 at Lloyd’s, steaming 14 knots; and she had accommodation for 432 passengers, of whom 84 were first class, 128 second class, and 220 steerage; and every berth was occupied, the steerage crowd consisting mostly of miners attracted to Australia by the rumour of a newly discovered goldfield of fabulous richness. The crew of the ship numbered, all told, 103; therefore, when the catastrophe occurred, the Saturn was responsible for the lives of 535 people, of whom about 120 were women and children.

I was officer of the watch, and was therefore on the bridge when it happened, the time being shortly after six bells in the middle watch, or say about a quarter past three o’clock in the morning. The weather was fine, with so moderate a westerly wind blowing that the speed of the ship just balanced it, the smoke and sparks from the funnel rising straight up into the air when the firemen shovelled coal into the furnaces; and apart from the long westerly swell there was very little sea running. The motion of the ship was therefore very easy, just a slow roll of four or five degrees to port and starboard, and an equally slow, gentle rise and fall of the ship over the swell that followed us. The moon was only four days old, consequently she had set hours earlier, but the sky was cloudless, the air was clear, and the stars, shining brilliantly, afforded light enough to reveal a ship at a distance of quite three miles; it would be difficult, therefore, to imagine conditions of more apparently perfect safety than those at the moment prevailing aboard the Saturn. Yet destruction came upon us in a manner, and with a suddenness, that was absolutely appalling.

I was pacing the bridge from one extremity to the other, keeping a sharp look-out ahead and all round the ship; and when, at the port end of my promenade, I wheeled on my return march, there was no sign that but a few minutes intervened between us and eternity. But as I approached the wheel-house I became aware of a sudden access of light in the sky behind me, illuminating the entire ship in a radiance that increased with incredible rapidity, while at the same moment a low humming sound became audible that also grew in volume as rapidly as the light. Wheeling sharply round, to ascertain the meaning of this strange phenomenon, I heard the helmsman ejaculate, through the open window of the wheel-house:

“Gosh! that’s a big ’un, and no mistake; the biggest I ever seen; and,”—on a note of sudden alarm—“it ain’t goin’ to fall so very far away from us, neither! D’ye see that big fireball, sir, headin’ this way?”

As the man spoke I caught sight of the object to which he referred—and horror chilled me to the marrow; for never before, I verily believe, had mortal eyes beheld so awful an apparition. Broad over the port bow, at an elevation of some forty degrees above the horizon, I beheld a great white-hot flaming mass, emitting a long trail of brilliant sparks, coming straight for the ship. It was increasing in apparent size even as I gazed at it, dumb and paralysed with terror indescribable, while the sound of its passage through the air grew, in the course of a second or two, from a murmur to a deafening roar, and the light which it emitted became so dazzling that it nearly blinded me as I looked at it. As it came hurtling toward us it seemed to expand until it looked almost as big as the ship herself; but that was, of course, an optical illusion, for when, a second or two later, it struck us, I saw that the fiercely incandescent mass, of roughly spherical shape, was some twelve feet in diameter.

It struck the ship aslant, on her port side, a few feet abaft the funnel and close to the water-line, passing through the engine-room and out through her bottom. There was no perceptible shock attending the blow, but the crash was terrific, while the smell of burning was almost suffocating—which is not to be wondered at, since the mass was blazing so fiercely that it set the ship on fire merely by passing through her. So intense was the heat of it that, as it passed through the ship’s bottom into the water, we instantly became enveloped in a dense cloud of hot, steamy vapour. A moment later it exploded under us, throwing up a cone of water that came near to swamping the ship.

For a space of perhaps two seconds after the passage of the meteor through the ship’s hull the silence of the night continued, and then, as though in response to a signal, there arose such a dreadful outcry as I hope never to hear again; while the cabin doors were dashed open, and out from the cabins and the companion-ways streamed crowds of distracted men, women, and children, clad in their night gear, just as they had leapt from their berths, the men shouting to know what had happened, while the poor women and children rushed frantically hither and thither, jostling each other, wringing their hands, some weeping, some screaming hysterically, and some calling to children who had become separated from them in the seething crowd.

The first man to run up against me was the skipper, who sprang out of his cabin straight on to the bridge, exclaiming, as he clutched me by the arm:

“What is it? What has happened? For God’s sake speak, man!”

“The ship,” I answered, “has been struck by an enormous meteorite, sir, which has set her on fire, I believe, and has passed out through her bottom. She has taken a perceptible list to starboard already.”

At this moment I was interrupted by the chief engineer, who dashed up on the bridge, demanding breathlessly: “Where is the captain?”

“I am here, Mr Kennedy. What is the news? Out with it!” jerked the skipper.

“My engines are wrecked, sir; utterly destroyed,” answered Kennedy; “and the ship is holed through her bottom, down in the engine-room. The hole is big enough to drive a coach through, and the room is half-full of water already. If either of the bulkheads goes we shall sink like a stone!”

At this juncture we were joined by the chief, second, and third officers, who came upon each other’s heels.

“Ah! here you are, gentlemen,” remarked the skipper. “I was about to send for you. I learn from Mr Blackburn that the ship has been struck by a falling meteor which, Mr Kennedy tells me, has passed through her bottom. According to him the engine-room is flooded; and he is of opinion that if either of the engine-room bulkheads yields the ship will go down quickly—in which opinion I agree with him. Even as it is, you may notice that the ship is taking a strong list, and is very perceptibly deeper in the water; therefore I will ask you, Mr Hoskins,” (to the chief officer) “and you, Mr Cooper,” (to the second) “to muster the hands, proceed to the boat-deck, and clear away the boats, ready for lowering, in case of necessity. You, Mr Stroud,” (to the third officer) “will mount guard at the foot of the boat-deck ladder and prevent passengers passing up until the boats are ready and I give the word. Mr Blackburn, go down and find the purser; tell him what has happened, what we are doing, and ask him to keep the people quiet until we are ready for them, and you can lend him a hand. Thank God, the boats are all provisioned, ready for any emergency, while the water in them was renewed only yesterday, so there is nothing to do but cut them adrift and swing them outboard. That is all at present, gentlemen, so go and get to work at once—why, who are those men on the boat-deck now, and what are they doing with the boats?”

“Looks like the miners,” answered Hoskins. “They’re a rough lot, and as likely as not we may have trouble with ’em. Ay, I thought so! Our chaps are up there too, trying to send the others away, and they don’t seem inclined to go. Come along, Cooper, we’ve got to clear those miners off somehow, or we shall get nothing done.”

Therewith the four of us departed upon our respective missions, leaving the captain in charge on the bridge.

The decks were now full of people rushing aimlessly hither and thither, stopping everybody they met, and asking each other what had happened. Meanwhile all the electric lights had been switched on, so that it was possible to see who was who, and, as I quite expected, no sooner did those poor distracted creatures catch sight of my uniform than I was surrounded, hemmed in by a crowd who piteously besought me to tell them what had happened, and if there was any danger. I had by this time quite recovered my self-possession, and was therefore able to answer them calmly and with a steady voice. Naturally, I did not tell them the whole truth, for that, I knew, would precipitate a panic in which everybody would get out of hand. I therefore told them there had been a breakdown in the engine-room, which was being attended to; that there was no immediate danger, but that I strongly advised them, purely as a measure of precaution, to return to their cabins, dress themselves warmly, and put into their pockets, or into parcels, any money or valuables they might have in their baggage, so that in the event of anything untoward happening, whereby we might be compelled to take to the boats, they would be prepared to do so at a moment’s notice. Some of them listened to me and allowed themselves to be persuaded, but others seemed afraid to leave the deck for a moment lest they should be overtaken by calamity.

After all, their apprehension was not to be wondered at; there was excuse enough for it, and to spare. There was a very strong smell of burning and occasional puffs of smoke coming up from below, where the engine-room staff were fighting the flames. The ship had taken a heavy and steadily-increasing list to starboard; she was visibly settling in the water; and, to crown all, the crowd of miners who upon the first alarm had taken possession of the boat-deck were refusing to leave it, and a brisk struggle between them and the seamen was proceeding, though as yet no firearms were being used. But I knew Hoskins’s temper; he was by no means a patient man, or one given to much verbal argument. It was usually a word and a blow with him, and not infrequently the blow came first; I knew also that he habitually carried a revolver in his pocket when at sea. I should not, therefore, have been at all surprised to hear the crack of the weapon at any moment.

I had just managed to extricate myself from the crowd, and was making my way toward the purser’s cabin, when from the interior of the ship, and almost beneath my feet, there came a deep boom, and I knew that the after bulkhead of the engine-room had given way, and that the moments of the Saturn were numbered.

“No use to hunt up the purser, now,” I thought; and I made a dash for the boat-deck, to see if I could render any assistance there. But I was too late; the sound of the bursting bulkhead, coming on top of the previous alarms, was all that was needed to produce the panic I had all along been dreading, and in an instant the decks were alive with frantic people, all desperately fighting their way upward to the boat-deck, where pandemonium now raged supreme, and where pistols were popping freely, showing that Hoskins was by no means the only man in the ship who went armed.

Now, what was the best thing for me to do? Could I do anything useful? I stood on the outskirts of that seething, maddened crowd, and watched men and women striving desperately together, trampling each other remorselessly down; shrieking, cursing, fighting; no longer human, but reduced by the fear of death to the condition of rabid, ferocious brutes. No, I could do nothing: as well go down below and attempt to stay the inrush of water with my two hands, as strive by argument to restore those people to reason; while, as for force, what could my strength avail against that of hundreds? No, they had all gone mad, and, in their madness, were destroying themselves, rendering it impossible to launch the boats, and so dooming themselves and everybody else to death. It was awful! That scene often revisits me in dreams, even to this day, and I awake sweating and trembling with the unspeakable horror of it.

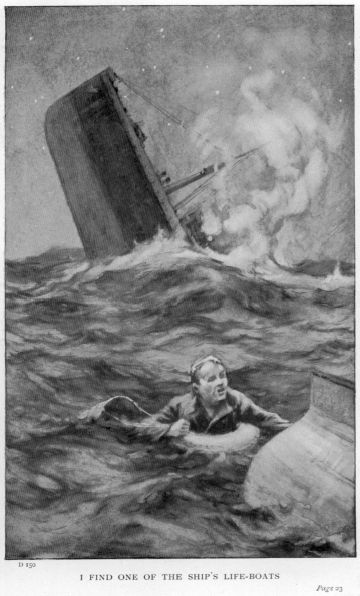

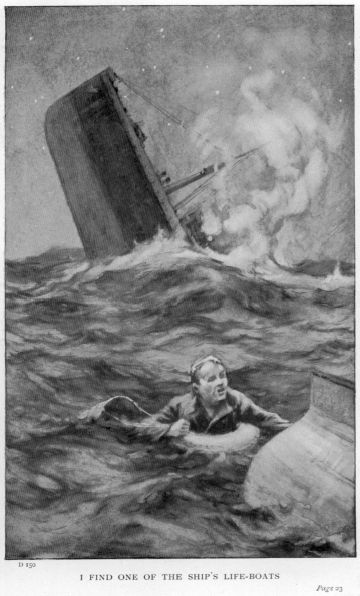

Meanwhile the ship was rapidly sinking; she had taken so strong a list to starboard that it was only with the utmost difficulty I could retain my footing upon her steeply inclined deck, while she was so much down by the stern that the sea was almost level with the deck right aft. Scarcely knowing what I did, acting with the inconsequence of one in a dream, I clawed my way across the bridge that led from the upper deck to the poop, and reached the taffrail, where I stood gazing blankly down into the black water, thinking, I am afraid, some rather rebellious thoughts. I must have stood thus for at least five minutes before I realised that my hands were gripping a life-buoy, one of six that were stopped to the rail. Still acting mechanically, and with no very definite purpose, I drew forth my pocket-knife, severed the lashing, passed the buoy over my head and shoulders, thrust my arms through it, climbed the rail—and dropped into the water.

The chill of the immersion instantly brought me to my senses. In a moment I realised that if I would save my life I must, without an instant’s delay, put the greatest possible distance between the ship and myself before she foundered, otherwise when she sank—which she might do at any moment—she would drag me down with her, and drown me. The desire to live, which seemed to have been paralysed within me by the suddenness of the disaster and the dreadful scenes I had subsequently witnessed, re-awoke, and I struck out vigorously.

I know not how long I had been swimming—it seemed to me, in my anxiety to get well away from the ship, to have been but a very few minutes—when the tumultuous sounds of contention aboard the doomed Saturn suddenly changed to a long wailing scream, and, glancing back over my shoulder, I saw, upreared against the star-lit sky, the fore end of the ship standing almost vertically out of the water, while at the same instant another loud boom reached my ears, proclaiming either the bursting of the ship’s boilers, the yielding of another bulkhead, or, possibly, the blowing up of her decks; then, as I paused for a moment to watch the conclusion of the catastrophe, the hull sank lower and lower still in the water until within the space of a minute it completely vanished.

The dreadful sight stimulated me to superhuman exertion, for I believed I was still perilously near that great sinking mass; and indeed I had scarcely covered another dozen yards when I felt the strong suction of the foundering ship. I fought against it with desperate energy, and in about a minute’s time it relaxed, and I ceased swimming.

“Now,” I asked myself, “what is the next thing to be done? I suppose it was instinct that prompted me to get into this life-buoy and swim away from the sinking ship; but in doing so have I not merely exchanged a quick for a lingering death? If I had stuck to the ship I should have gone down with her, and died with very little suffering, if any; while, so far as I can see, I am now fated to drift about in this buoy until I perish slowly and miserably of cold, hunger, and thirst.”

It was a most depressing reflection, and for a moment I felt strongly tempted to slip out of the buoy, throw up my hands, sink, and have done with it. But no; love of life, self-preservation, which we are told is the first law of nature, would not permit me to act foolishly; reason reasserted herself, reminding me that while there is life there is hope. I remembered that I was floating in a stretch of water that is the highway for ships bound round the Cape to and from Australia and New Zealand. It is a highway that, if not quite so busy as London’s Fleet Street, is traversed almost daily by craft of one sort or another, bound either east or west; and something might come along at any moment and, if I could but attract attention to myself, pick me up. Besides, I did not really believe in “giving up”. It had been instilled into me from my earliest childhood that the correct way to meet difficulties is to fight them, and to fight the harder the more formidable appear the difficulties. And the doctrine is sound; I had and have proved it to be so, over and over again, and I meant again to put it to the test, then, in the most discouraging combination of adverse circumstances with which I had ever been confronted.

But the water was bitterly cold; if I remained submerged to my armpits, as I then was, I could not survive long enough to get a fair chance. I needed a raft of some sort buoyant enough to support me practically dry; and, remembering that there were numerous loose articles such as deck-chairs, gratings, and what not that would probably float off the wreck when she sank, I turned and swam back towards the spot where the Saturn had gone down, hoping that I might be fortunate enough to find something that would afford me the support I required. And as I struck out afresh I was cheered and encouraged by the assurance that day was not far distant, for, looking ahead, I saw that the sky low down toward the horizon wore the pallor that is the forerunner of dawn.

By imperceptible degrees the day crept up over the eastern horizon, cold and white; and, as soon as there was light enough to enable me to see from the crest of one swell to that of the next, I began to look about me in the hope of finding flotsam of some sort that would be useful to me; also it occurred to me that there might be some who had remembered that cork jackets were to be found in every state-room, and might have made use of them; in which case I might fall in with other survivors, who might be useful to me, and I to them, if we joined forces.

For several minutes my search of the surface of the sea proved fruitless, at which I was distinctly disconcerted, for I knew that there were many articles of a buoyant nature which had been lying loose about the decks, and which must have floated off when the ship sank; and I was beginning to fear that somehow I had got out of my reckoning and had missed the scene of the catastrophe. But a minute or two later, as I topped the ridge of a swell, I caught a momentary glimpse of something floating, some fifty or sixty fathoms away, and, striking out vigorously in that direction, I presently arrived at the spot and found myself in the midst of a small collection of brooms,  scrubbing-brushes, squeegees, buckets, deck-chairs, gratings, and—gigantic slice of luck!—one of the ship’s life-boats floating bottom up! But of human beings, living or dead, not a sign; it was therefore evident that, of the five hundred and thirty-five aboard the Saturn at the moment of the disaster, I was the sole survivor.

scrubbing-brushes, squeegees, buckets, deck-chairs, gratings, and—gigantic slice of luck!—one of the ship’s life-boats floating bottom up! But of human beings, living or dead, not a sign; it was therefore evident that, of the five hundred and thirty-five aboard the Saturn at the moment of the disaster, I was the sole survivor.

Naturally, I made straight for the upturned life-boat; but recognising that a bucket might prove very useful I secured one and towed it along with me. Reaching the boat I was greatly gratified to find that not only was she quite undamaged but also that she was riding buoyantly, with the whole of her keel and about a foot of her bottom above the surface of the water. Of course the first thing to be done was to right the boat, and then to bale her out; and, with the water as smooth as it then was, I thought there ought not to be much difficulty in doing either. The righting of the boat, however, proved to be very much more difficult than I had imagined. She was a fairly big boat and, floating wrong side up and full of water, she was very sluggish, and for a long time scarcely responded to my efforts; but I eventually succeeded, and, with a glad heart, seized the bucket I had secured, hove it into the boat, and climbed in after it, finding to my joy that, even with my weight in her, the boat floated with both gunwales nearly four inches above the surface of the water. Thus there would be no difficulty in baling her dry; and this I at once proceeded to do, working vigorously at the task, not only with the object of freeing the boat as speedily as possible, but, still more, to restore my circulation and get a little warmth into my chilled and benumbed body.

Chapter Two.

The “Yorkshire Lass.”

By the time that I had baled the boat dry the sun was above the horizon, the air had become quite genially warm, and my exertions had set my body aglow, while my clothing was rapidly drying in the gentle breeze that was blowing out from about north-west; also I discovered that I had somehow developed a most voracious appetite.

Fortunately, I was able to regard this last circumstance with equanimity, for the manager of the Planet Line of steamers had laid it down as a most stringent rule that while the ships were at sea all boats were not only to be maintained in a state of perfect preparation for instant launching, but were also to be fully supplied with provisions and water upon a scale proportional to their passenger-carrying capacity, and each was also to have her full equipment of gear stowed in her, ready for instant service. Now, the boat which I had been fortunate enough to find—and which, by the way, seemed to be the only one that had not been carried down with the ship—was Number 5, a craft thirty-two feet long by eight feet beam, carvel-built, double-ended, fitted with air-chambers fore and aft and along each side, with a keel six inches deep to enable her to work to windward under sail. She was yawl-rigged, pulled six oars, and her full carrying capacity was twenty-four persons, for which number she carried provisions and water enough to last, according to a carefully regulated scale, four days, or even six days at a pinch. These provisions were all of the tinned variety, and were stowed in a locker specially arranged for their reception between the two midship thwarts. Thus there was no risk of the food being damaged by salt water, on the one hand, or of being washed out of the boat, on the other. Upon coming into possession of the boat, therefore, I was not only so fortunate as to find an ark of refuge, but also rations of food sufficient to last me ninety-six days.

Knowing all this—such knowledge being a part of my duty—no sooner had I hove the last bucketful of water out over the gunwale than I opened the food locker and spread the constituents of a very satisfying breakfast in the stern-sheets of the boat; whereupon I fell to and made an excellent meal.

As I sat there, eating and drinking, a solitary individual adrift in the vast expanse of the Southern Ocean, I began to look my future in the face and ask myself what I was now to do. In a general sense it was not at all a difficult question to answer. The Saturn, that splendid, new, perfectly equipped steamship, had gone to the bottom, taking with her five hundred and thirty-four human beings; and, apart from myself and the boat I sat in, there was nothing and nobody to tell what her fate had been. I was the sole survivor of a probably unexampled disaster, and my obvious duty was to hasten, with as little delay as possible, to some spot from which I could report the particulars of that disaster to the owners of the ship.

But what spot, precisely, must I endeavour to reach? As an officer of the ship I of course knew her exact position at noon on the day preceding her loss. It was Latitude 39 degrees 3 minutes 20 seconds South; Longitude 52 degrees 26 minutes 45 seconds East; I remembered the figures well, having something of a gift in that direction, which I had sedulously cultivated, in view of the possibility that some day I might find it exceedingly useful. In the same way I was able to form a fairly accurate mental picture of the chart upon which that position had been pricked off, for Cooper, our “second”, and I had been studying it together in the chart-house shortly after the skipper had “pricked her off”. As a result, I knew that the Saturn had foundered some two thousand miles east-south-east of the Cape of Good Hope; that Madagascar—the nearest land—bore about north-by-west, true; with the islands of Reunion and Mauritius, not much farther off, bearing about two points farther east. These items of information were of course valuable; but their value was to a very great extent discounted by the fact that I had neither sextant nor chronometer wherewith to determine the boat’s position, day after day, nor a chart to guide me.

At this point in my self-communion I realised that alternative courses were open to me, and I proceeded to give them my most careful consideration, comparing the one with the other. And the more carefully I examined them, the more difficult did I find it to come to a decision. On the one hand, here was I, right in the track of ships bound east and west; consequently I stood a very fair chance of being picked up at any moment, when the ship’s wireless installation would at once enable me to make my report. On the other hand, in the unlikely event of my failing to be picked up, I could dispatch a cablegram from, say, Port Louis, Mauritius, immediately upon my arrival there; and the point which I had to decide was whether I should at once steer north, or whether I should remain where I was, and trust to being speedily picked up. I will not weary the reader by repeating in detail the arguments, pro and con, that presented themselves to my mind; let it suffice me to say that I eventually adopted the second of the courses outlined above. And so certain did I feel that this was the right decision that I actually adhered to it for seven days, during which I sighted four steamers and one sailing ship; but, as ill-fortune would have it, three of the steamers and the sailing ship passed me at too great a distance to permit of my intercepting them, while the fourth steamer—a big liner, with three tiers of ports blazing with electric light—passed during the night, within less than four miles of me; but I had no light with which to signal to her, and thus I was passed unseen.

The liner passed me during the fifth night succeeding that of the wreck; and during the following two days I saw nothing. As I watched the sun go down on the seventh day that I had spent in the boat I said to myself:

“Well, here endeth the seventh day of a most disappointing experience. If, seven days ago, anyone had told me that I could hang about here in a boat for a whole week, right in the track of ships, without being sighted and picked up, I would not have believed it. Yet here I am, and, judging from past experience, here I may remain for another seven days, or even longer, with no more satisfactory result. I have spent seven precious days waiting for a ship to come along and find me; now I will go and see if I cannot find a ship, or, failing that, find land, where I shall at least be safe from destruction by the first gale that chances to spring up.”

Thinking thus, I put up my helm, wore the boat round, and headed her upon a course that I believed would eventually enable me to hit off either Reunion or Mauritius, should I not be picked up beforehand.

That was a very anxious night indeed for me; by far the most anxious that I had thus far spent since the destruction of the Saturn, for the wind steadily increased, compelling me to haul down a first and then a second reef in the mainsail, while—the wind and sea being now square abeam—I was continually exposed to the danger of being swamped by a sea breaking aboard. By constant watchfulness, however, I contrived to escape this danger, and my eighth morning found the boat bowling along to the northward and reeling off her six knots per hour, with a steady breeze from the westward, a long, regular sea running, and a clear sky giving promise that the weather conditions were unlikely to grow any worse than they were then. But I had to stick to the mainsheet and the yoke-lines, and do as best I could without rest, for the time being. Fortunately, as the day wore on, the wind moderated, until by nightfall it had dropped to such an extent that I was able to shake out first one reef and then the other, while with the moderating of the breeze the sea also went down until it was no longer dangerous.

I had now had no sleep for thirty-six hours, consequently I felt in sore need of rest. I therefore hove-to the boat, coiled myself down, and instantly sank into a dreamless slumber. It must have been about midnight when I awoke. I at once let draw the fore-sheet, filled away upon the course I had decided upon, and kept the boat going for the remainder of the night.

The ninth day of my boat voyage dawned pleasantly, with the wind still blowing a moderate breeze from the westward, a long, regular swell running, and no sea worth troubling about. The conditions were therefore quite favourable for a little experiment I desired to make. Being only human, I could not avoid the necessity for securing a certain amount of sleep, and, up to now, when I needed rest it had been my habit to heave-to the boat and leave her to take care of herself, trusting to that curious sailor-sense, which all sailor-men soon acquire, to awake me should the need arise. But heaving-to meant loss of time; and having already lost so much I was very reluctant to lose more, if such loss could possibly be avoided. I therefore set the boat going on her correct compass course, and then, releasing the yoke-lines, I endeavoured to render the craft self-steering by adjusting the fore and mizen sheets. It took me the best part of half an hour to accomplish this to my complete satisfaction, but I did it at length and, this done, I went aloft and took a good look round. There was nothing in sight—indeed I scarcely expected to see anything in the part of the ocean which I had then reached; I therefore descended and rested until dinner-time, indulging in another nap until the hour for my evening meal, in preparation for an all-night watch.

The weather had now become quite settled, and was as favourable as it could possibly be to persons who, like myself, were engaged upon an ocean voyage in an open boat. The wind still held steadily in the western quarter, enabling me to lay my course with eased sheets, while its strength was sufficient to push the boat along under whole canvas at a speed of about five knots, with no need to keep one’s eye continually watching the lee gunwale. My only difficulty at this time was the lack of a light to illuminate the boat compass at night, the can containing the supply of lamp oil seeming to have gone adrift when the boat was capsized. I was therefore compelled to steer entirely by the stars, and I was sometimes disturbed by an uneasy doubt as to whether I might not occasionally have deviated slightly from my proper course by holding on to one particular star for too long a time. In all other respects I did splendidly.

The morning of the tenth day of this remarkable but, on the whole, uneventful voyage of mine in the life-boat dawned auspiciously, and the daily routine into which I had settled began. I went aloft for a look round, and then, the horizon being empty, I had breakfast; after which, with the boat steering herself, I stretched myself out for a short sleep.

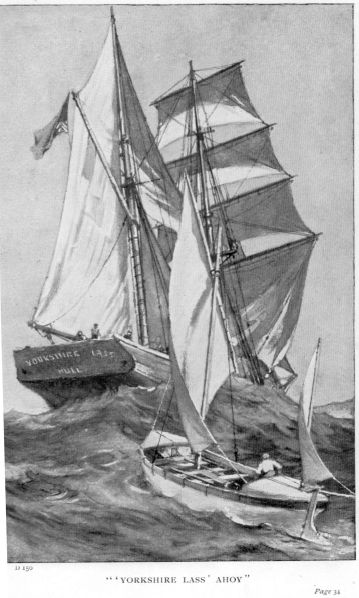

I must have slept for perhaps two hours when some mysterious influence awoke me, and I started up, gazing eagerly about me. There was still nothing in sight from the low elevation of the boat herself, but being awake I decided to have a look round from aloft. In another minute I was straddling the yard of the main lug, from which position, as the boat floated up on a ridge of swell, I caught a momentary glimpse of something gleaming white in the brilliant sunshine right ahead. It could, of course, be but one thing, namely, the upper canvas of a sailing craft of some sort. I remained where I was, intently watching that gleaming white speck until it had grown into the semblance of a royal and the head of a topgallant sail. From time to time I also got occasional glimpses of the upper part of another sail which I could not for the moment identify; but ultimately, as I watched, the strange craft seemed to alter her course a little, and then I made out the puzzling piece of canvas to be the triangular head of a gaff-topsail; the vessel was therefore, without a doubt, a brigantine. What I could not at first understand, however, was the way she was steering; at one moment she would appear absolutely end-on, while a minute or two later she would be broad off the wind, to the extent of four or five points. It was exceedingly erratic steering, to say the least of it, and I was tantalised too by my inability to determine whether she was heading toward or away from me; but eventually I decided that, since her masts had hove up above the horizon just where they were, she must be heading toward me. The only argument against this assumption was that she did not appear to be rising rapidly enough to justify it; but  she certainly was rising, although slowly, and that was enough for me in the meantime. Without further ado, therefore, I slid down from aloft, went aft, and seized the yoke-lines, saying to myself:

she certainly was rising, although slowly, and that was enough for me in the meantime. Without further ado, therefore, I slid down from aloft, went aft, and seized the yoke-lines, saying to myself:

“I believe it’s going to be all right this time. She is a sailing craft and I am raising her, although very slowly. It will be afternoon before I can get alongside her, but, please God, there will be no more open boating for me after to-day.”

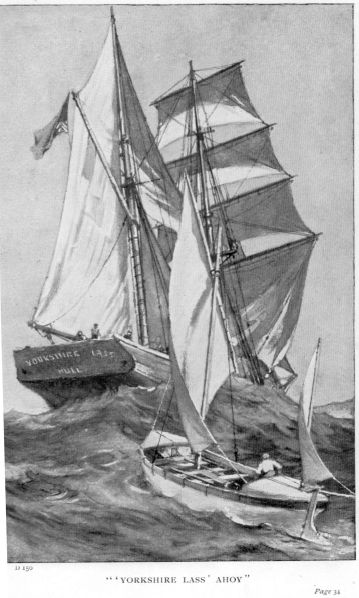

That the craft in sight was indeed a brigantine became unmistakable as I stood on, slowly raising her canvas above the horizon; and later on in the day I made two further discoveries, of a rather peculiar character, in connection with her. One was, that she was hove-to; the other, that she was flying her ensign upside-down at the peak of her mainsail, the latter circumstance indicating that she was in distress or required assistance of some kind.

It was about three o’clock in the afternoon when the life-boat crept up near enough to the brigantine to enable me to distinguish details; and the first thing I observed was that a group of five or six men—apparently forecastle hands—were grouped aft, curiously inspecting the boat through a telescope as I approached. A little later, when I arrived within a few fathoms of her, I learned, from the inscription in white letters on her stern, that the craft was named the Yorkshire Lass, and that she hailed from Hull.

As I drew up within hail I put my hands to my mouth, trumpet-wise, and shouted:

“Yorkshire Lass ahoy! I am a castaway, and have been adrift in this boat ten days. May I board you?”

To my amazement, instead of replying, the group of men clustered on deck aft turned to each other and seemed to hold a brief consultation. Finally, after a short palaver, one of them hailed:

“Boat ahoy! I say, mister, are you a navigator?”

“Yes, certainly,” I replied, much astonished at having such a question addressed to me by a British seaman, instead of—as I had fully expected—receiving a cordial invitation to come alongside; “I was fourth officer of the Saturn, of the Planet Line of steamers running between London and Melbourne—” and then I stopped, for instead of listening to me they were all talking together again. At length, when the life-boat had crept up close under the brigantine’s lee quarter, one of the men came to the rail and, looking down into the boat, remarked:

“All right, mister; come aboard, and welcome. Look out, and I’ll heave ye a line.”

A couple of minutes later the life-boat, with her sails lowered, was alongside, and, climbing the craft’s low side, I reached her deck.

“Welcome aboard the Yorkshire Lass, mister,” I was greeted by a great burly specimen of the British “shellback”, as I stepped in over the rail. “Very glad to see ye, I’m sure. But what about your boat? She’s a fine boat and no mistake; but I’m afraid we’ll have to let her go adrift. She’s too big for us to hoist her in; we’ve no place on deck where we could stow her. But if there’s anything of value aboard her we’ll have it out, eh, mister?”

“Certainly,” I agreed. “There is still a quantity of preserved provisions in that locker; there are the two water breakers; there is a life-buoy—and that is about all. But, look here!” I continued; “if something must be turned adrift, why not get rid of that long-boat of yours, and hoist in the life-boat in her place? The latter is very much the better boat of the two—there is indeed no comparison between them—and I am sure she would stow very snugly in your long-boat’s chocks.”

“Ay,” agreed the other, “I believe she would. And, as you say, she’s a lot better than the long-boat; she’ve got air-chambers, I see, and—in fact she’s a proper life-boat, and she’s roomy enough to take all hands of us if anything should happen. What say, chaps, shall us try it?”

This last to the other men, who had stood around listening to everything that was said.

The party, five of them in all, slouched over to the rail and stood looking down into the life-boat with an air of stolid indifference, as she rose and fell alongside. Then they turned and looked inboard at the long-boat, which stood upright in chocks, on top of the main hatch, with the jolly-boat stowed, keel-up, inside her. Finally one of them said:

“Yah, ve’ll do id; she’s wort’ de drouble. Gome on, poys, led’s ged do vork; we haven’d done moosh dese lasd dwo days, und id von’d hurd us. Shoomp ub dere, zome of you und ged de sholly-boad oud of dad!”

“Now,” thought I, “what sort of a craft is this that I’ve blundered aboard of? She’s Liberty Hall afloat, by the look of it—Jack as good as his master! There seems to be something a bit queer here—something that I can’t quite understand at present, but I’ll find out what it is before long. Which of those fellows is the skipper, I wonder—or, if neither of them is, as I am very much inclined to think, where is he?” And then I suddenly recalled to mind the question—“Are you a navigator?”—which had been put to me before I received permission to come aboard. For a moment I thought of demanding an explanation before permitting the life-boat to be hoisted in; but I changed my mind and resolved to defer my investigation until later. I flattered myself that if anything should prove to be really wrong aboard the brigantine I had wit enough to enable me to deal with it.

Meanwhile, the five men, having summoned three others from the forecastle to their assistance, got to work with the exasperating deliberation characteristic of the British merchant seaman to be found in the forecastles of small craft; and first of all they got the jolly-boat down on deck and ran her aft, out of the way; then they cleared out a number of warps, cork fenders, and other lumber from the long-boat, lifted her out of her chocks, and finally, unshipping the gangway, launched her overboard, fisherman-fashion, and dropped her astern, riding to her painter. Then they got their mast and yard tackles aloft, arranged the chocks in place on the main hatch, and with a tremendous amount of fuss, with the assistance of snatch-blocks, the windlass, and the winch, they contrived to hoist in and stow the life-boat that had stood me in such good stead for nearly a fortnight. That done, all hands held another somewhat lengthy and animated pow-wow on the forecastle-head, at the conclusion of which the man who had given me permission to come aboard came aft and, pointing to the life-boat, remarked to me:

“I reckon we’ve made a very good job of that, mister, and I’m sure we’re all very much obliged to ye for the idee. She’s worth a dozen of the long-boat and quite worth all the trouble we’ve took to put her where she is.” Then, without waiting for any response, he stepped aft, peered through the skylight, and, stepping to where the ship’s bell hung, he struck eight bells (four o’clock). Rejoining me as I stood watching the long-boat, that had been cast adrift, he remarked, with a clumsy effort at civility:

“Tea’ll be coming along aft in about five minutes, and I reckon you’ll be glad of a cup. I s’pose you haven’t been gettin’ much hot food while you’ve been moochin’ about in that boat, have ye?”

“I have not,” I replied. “It was impossible to do cooking of any kind, as of course you will readily understand.”

“Ah, well, ye’ll be able to make up for it now,” was the rejoinder, “for here comes the steward, teapot and all. Step down below into the cabin, and make yourself at home.”

“Many thanks,” said I. “By the way, are you the master of this vessel? And I gather from your ensign being hoisted union-down that you are in distress. What is wrong with you?”

Chapter Three.

An Amazing Story.

We were now passing down the companion ladder on our way to the cabin, and as I finished speaking the man to whom I addressed my question, and who had led the way below, motioned me to enter an open doorway at the foot of the stairs.

Obeying the invitation, I found myself in a small, rather dark and stuffy cabin, very plainly fitted up; the woodwork painted dark-oak colour, the beams and underside of the deck planking overhead imparting a little cheerfulness to the small interior by being painted white, while the lockers were covered with cushions of much worn plush that had once been crimson, but which, through age, wear, and dirt, had become almost black. The place was lighted by a small skylight in the deck, and two ports, or scuttles, on each side. At one end of the skylight was screwed a clock, while to the other end was screwed a mercurial barometer hung in gimbals; and immediately over the chair at the fore end of the table hung a tell-tale compass. The table was laid with a damask table-cloth that had seen better days, and, no doubt, had once been white, while the ware was white and of that thick and solid character that defies breakage. A well-filled bread barge, containing ordinary ship biscuit, stood at one end of the table, flanked by a dish of butter on one side and a pot of jam on the other; the tray was placed at the starboard side of the table, and amidships, at the fore end, there stood a dish containing a large lump of salt beef behind three plates, with a carving knife and fork alongside them. To the chair in front of these, or at the head of the table, the man who was acting the part of host now waved a hand, mutely inviting me to take it.

“Certainly not,” I said. “You are the master of the ship, I presume, and, as such, this is of course your rightful place. Why should you surrender it to me?”

“Ah, but that’s just where you make a mistake, Mr—er—er—I forget your name. No, I’m not the skipper; I’m the bosun, and my name’s Enderby—John Enderby. And this man,”—indicating an individual who at this moment joined us—“is William Johnson, the carpenter—otherwise ‘Chips’.”

“Then, where is your skipper—and your mate?” I demanded.

“That’s what we’re in distress about,” answered the boatswain. “Sit down, sir, please, and let’s get on with our tea; and while we’re gettin’ of it I’ll spin ye the yarn. That’s why me and Chips is havin’ tea down here, aft, this afternoon. At other times we messes with the rest of the men in the fo’c’sle; but as soon as you comed aboard we all reckernised that you’d want to know the ins and outs of this here traverse that we finds ourselves in, so ’twas arranged that me and Chips should have tea with ye, and explain the whole thing.”

“I see,” said I. “Well, you may heave ahead while I carve this beef. I can do that and listen at the same time.”

“Yes,” assented Enderby. Then, breathing deeply, he gazed steadfastly at the clock for so long a time and with an air of such complete abstraction that at length Chips, who was sitting on the locker alongside him, gave him an awakening nudge of the elbow, accompanied by the injunction:

“Heave ahead, man; heave ahead! You’ll never get under way if you don’t show better than this.”

“Ay, you’re right there, my lad, I shan’t, and that’s a fact,” returned Enderby. “The trouble is that I don’t know where to make a start—whether to begin with what happened the night afore last, or whether ’twould be best to go back to our sailin’ from London.”

“Perhaps the last will be the better plan,” I suggested. “If you start at the very beginning I shall stand a better chance of understanding the whole affair.”

“Ay, ay; yes, of course you will,” agreed the boatswain. “Well, it’s like this here,” he began. “We left London last September—you’ll find the exact date in the log-book—with a full cargo for Cape Town, our complement bein’ thirteen, all told. Thirteen’s an unlucky number, mister; and as soon as I reckernised that our ship’s company totted up to that I knowed we should have trouble, in some shape or form. But we arrived at Cape Town all right; discharged our cargo; took in ballast; filled up our water tanks, and got away to sea again all right; and it wasn’t until the night afore last that the trouble comed along. Our skipper’s name was Stenson, and the mate called hisself John Barber, but I ’low it was, as likely as not, a purser’s name, for I never liked the man, and no more didn’t any of us, for though he was a good enough seaman he had a very nasty temper and was everlastin’ly naggin’ the men.

“It appeared that he and the skipper was old friends—or anyway they knowed one another pretty well, havin’ been schoolfellers together; and the story goes that some while ago this man, Barber, bein’ at the time on his beam-ends, runned foul of the skipper and begged help from him, spinnin’ a yarn about a lot of treasure that he’d found on an island somewhere away to the east’ard, and offerin’ to go shares if he’d help Barber to get hold of the stuff. I dunno whether the yarn’s true or no, but the skipper believed it, for the upshot of it was that Cap’n Stenson—who, I might say, was the owner of the Yorkshire Lass—hustled around and got a general cargo for Cape Town, after dischargin’ which we took in ballast and sailed in search of this here treasure. Well, everything worked all right until the night afore last, when Barber, who was takin’ the middle watch, went below and, for some reason or another, brought the skipper up on deck. Svorenssen, who was at the wheel, says that the pair of ’em walked fore and aft in the waist for a goodish bit, talkin’ together; and then suddenly they got to high words; then, all in a minute, they started fightin’ or strugglin’ together, and before Svorenssen could sing out or do anything they was at the rail, and the pair of ’em went overboard, locked in one another’s arms.”

“Went overboard!” I reiterated. “Good Heavens! what an extraordinary thing! And was no effort made to save them?”

“Svorenssen sung out, of course,” replied the boatswain, “but he couldn’t leave the wheel, for ’twas pipin’ up a freshish breeze on our port quarter, and we was doin’ about seven, or seven and a half knots, with topmast and lower stunsails set to port, and of course we had to take ’em in, clew up the royal and to’ga’ntsail, and haul down the gaff-tops’l before we could round to; and that took us so long that at last, when we’d brought the hooker to the wind, hove her to, and had got the jolly-boat over the side, we knowed that it’d be no earthly use to look for either of ’em. All the same, I took the boat, with three hands, and we pulled back over the course we’d come; as near as we could guess at it; but although we pulled about until daylight. We never got a sight of either of ’em.”

“What a truly extraordinary story!” I repeated. “And, pray, who is now in command of the ship?”

“Well, I s’pose I am, as much as anybody—though there haven’t been much ‘commandin’’ since the skipper was lost,” answered Enderby. “But I’m the oldest and most experienced man aboard, and the others have been sort of lookin’ to me to advise ’em what to do; and since there’s ne’er a one of us as knows anything about navigation I advised that we should heave-to, hoist a signal of distress, and then wait until something comed along that would supply us with a navigator. But now that you’ve comed along we needn’t waste any more of this fine fair wind, because I s’pose you won’t have no objection to do our navigatin’ for us, eh?”

“That depends entirely upon where you are bound for,” I replied. “Of course I shall be very pleased to navigate the ship to the nearest port on your way, but I cannot promise to do more than that. And you have not yet told me where you are bound. Did I not understand that it is to some island?”

“Ay, yes, that’s right,” answered the boatswain, “but,”—here he raised his voice to a shout—“Billy, come here, my lad, and tell the gen’leman what you knows about this here v’yage.”

Whereupon, to my astonishment, a very intelligent-looking boy, of apparently about eleven or twelve years of age, emerged from the pantry, where it appeared he had been helping the steward, and stood before us, alert and evidently prepared to answer questions. He was only a little chap, fair-haired and blue-eyed, and his eyelids were red, as though he had recently been crying; but there were honesty, straightforwardness, and fearlessness in the way in which he looked me straight in the eye, and an evident eagerness in his manner that greatly pleased me.

“This,” said Enderby, by way of introduction, “is Billy Stenson, the skipper’s son. He haven’t no mother, pore little chap, so he’ve been comin’ to sea with his father the last two or three years, haven’t you, Billy?”

“Yes, that’s quite right, bosun,” answered the boy.

“Well, now, this gentleman, Mr—er—dashed if I can remember your name, mister!” proceeded Enderby.

“Blackburn,” I prompted.

“Thank ’e, sir. Blackburn. Well, Billy,” continued the boatswain, “this here Mr Blackburn is a first-class navigator, havin’ been an orficer aboard a liner, and he’ll be able to take us to Barber’s treasure island, if anybody can. But, of course, he’ll have to know whereabouts it is afore he can navigate the ship to it; and now that your pore father’s—um—no longer aboard, I reckon that you’re the only one who can say what’s the latitood and longitood of it.”

“But that’s just what I can’t do, bosun,” answered Billy. “I know what the latitude of it is, but the longitude’s another matter. Mr Barber didn’t know it; Father didn’t know it; and I don’t know it.”

“What!” I exclaimed. “Do you mean to tell me that your father actually started out with the deliberate intention of looking for an island the latitude only of which he knew?”

“Yes, sir,” answered the boy, “that’s right. Let me tell you how it all happened. I know, because Father told me the story lots of times; and besides, I’ve heard him and Mr Barber talking about it so often that I’m not likely to forget a word of it. This is how it was:—

“Before Mr Barber met Father, this last time, he was mate of a Dutch ship trading out of Batavia, collecting sandalwood and shell. They called at a place named—named—Waing— Do you mind, sir, if I get the chart and show you the place on it? Somehow, I never can exactly remember the names of these places, but I can point ’em out on the chart, because I’ve listened and watched while Father and Mr Barber talked it over together.”

“Yes,” I said, “by all means get the chart, my boy. I shall be able to understand your story ever so much better with that before me.” Whereupon the lad entered a state-room at the fore end of the main cabin, and presently returned with a chart of the Malay Archipelago, which he spread open on the table.

“There,” he said, pointing with his finger, “that’s the place they called at—Waingapu, in Sumba Island; and this pencil-mark Mr Barber drew to show the track of the ship and the boat afterwards—as nearly as he could remember. After leaving Waingapu the ship sailed along this line,”—pointing with his finger—“through Maurissa Strait, up to here. And here Mr Barber and the Dutch captain had a terrible quarrel and a fight—I don’t know what about, because Mr Barber didn’t say, but it ended in Mr Barber being turned adrift by himself in a boat, with a small stock of provisions and one breaker of fresh water. The boat was an old one, very leaky, and she had no sail, so Mr Barber could do nothing but just let her drift, hoping every day that something would come along and pick him up. But nothing came, and five days later he found that his water was all gone, the breaker havin’ been leaky. The next thing that happened was that Mr Barker got light-headed with thirst; and it used to make me feel awfully uncomfortable to hear him tell about the things he thought he saw while he was that way. At last he got so thirsty that he couldn’t stand it any longer, and, bein’ mad, he filled the baler with water from over the side, and drank it. And then he found that the water was fresh, and he drank some more, and his senses came back to him, and, lookin’ round, he saw that there was land on both sides of the boat and that she was in a sort of wide river. But, although the land was so plain in sight, Mr Barber was so weak that he couldn’t do anything; for while he was light-headed he’d hove all his grub overboard and was now starving. So he just had to let the boat drift with the wind; and after a bit she drove ashore. But even then Mr Barber couldn’t do anything but just climb out of the boat and fling himself down upon the sand, where he slept until next morning.

“When he woke up he felt a bit better, but awfully hungry, so he got up and, seeing a few trees not far off, he managed to crawl over to ’em, and was lucky enough to find some fruit on ’em. He said he didn’t know what the fruit was, and didn’t care, he was so awfully hungry that he’d have eaten it, even if he’d known it was poison. But it wasn’t; it was quite good; and after he had eaten he felt so much stronger that he went back to the beach and moored his boat to a big boulder, so that she wouldn’t drift away.

“Now that Mr Barber had found food and water he set about taking care of himself, so that he might get strong again and be able to get away from where he was—because, of course, he didn’t want to spend the rest of his days there. But he wanted to find out as much as he could about the place; so as soon as he was strong enough he began to wander about a bit, explorin’, and in particular he wanted to have a look at something that he thought might be a house all overgrown with creepers. And when at last he was able to get to it he found that it was a very ancient ship, that he thought must have drove ashore during the height of a very heavy gale of wind, when the level of the sea surface was raised several feet above ordinary, deeply flooding the low ground where he found her.

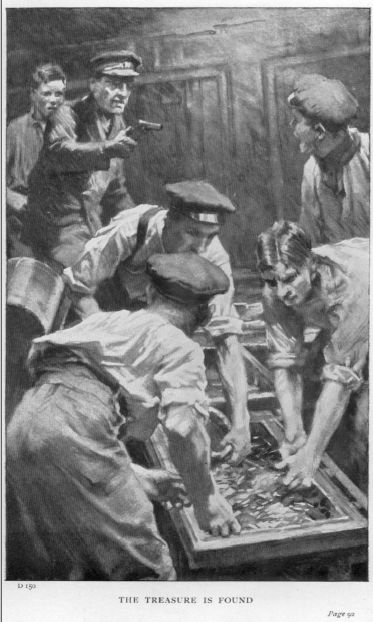

“Of course Mr Barber climbed aboard and had a good look round, thinking that he’d perhaps be able to take up his quarters aboard her until he could get away from the place; but he found her timbers and deck planking all so rotten that it wasn’t safe to move about aboard her. All the same, he gave her a good overhaul; and down in the run he found a little room, and in it eight big chests all bound round with thick, steel bands. With a lot of trouble he broke ’em open, and five of ’em he found packed full of gold and silver things—coins, candlesticks, images and things that he believed had been stolen out of churches, with chains and rings and bracelets and things of that sort. And the other three chests had in ’em all sorts of gems—diamonds, rubies, emeralds—and oh, I forget the names of all the things he said he found in them; but I remember he said that they looked as though they’d been broken out of articles of jewellery. Two of the chests were full, chock-a-block, and the other was about three-parts full; and he said that, altogether, the treasure must be worth millions!

“So as soon as Mr Barber felt well and strong enough to get away from the place, he caulked the seams of his boat, and his water breaker, with a kind of cotton that he found growing wild, made a mat sail for his boat out of grass, laid in a stock of fruit and water, and, taking a handful of the gems along with him, went out to sea again. But before leaving the place he got the meridian altitude of the sun, by setting a stick upright in the ground and measuring the length of its shadow very carefully several days running; and in this way he afterwards found that the latitude of the wreck was about 3 degrees 50 minutes South. Then, when he was satisfied that he’d got the position near enough to be able to find it again, he set his sail and went out to sea.

“But he was unlucky again, for on that very night a gale sprang up, his sail was blown away, and he had all his work cut out to keep the boat from being swamped. Then he fell ill again and went crazy once more, coming to himself again aboard a Chinese junk bound for Singapore. Of course the first thing he did was to search for his little packet of gems; but they were gone; and, although he strongly suspected the Chinese of having stolen them, they swore that they had seen nothing of them. At Singapore Mr Barber applied for help as a distressed sailor, and, after waiting a bit, he was sent home in a ship bound for London. Four days after he landed in London he met Father, who helped him by giving him money and inviting him to take up his quarters, for a bit, aboard the Yorkshire Lass. Then he told Father all about the treasure, and they kept on talkin’ about it every evenin’, when the day’s work was done, until at last Father agreed to help Mr Barber to search for the treasure, he and Mr Barber to go halves in everything they found, and Mr Barber to come with us as mate. And—and—I think, sir, that’s all.”

“And quite enough, too,” I said. “Why, it is the most amazing story to which I have ever listened. And do you really mean to say that your father actually allowed himself to be persuaded into engaging in such a wild-goose chase as that of hunting for a spot of which the latitude only is known—and that merely approximately, I should imagine.”

“Yes, indeed, sir, it is a fact,” answered Billy. “I know, because Father and Mr Barber drew up an agreement and signed it, Father keeping one copy, and Mr Barber the other. Father’s copy is in his desk now, if you’d care to see it.”

“Later on, perhaps,” I said. “There are other and more pressing matters requiring attention just now. This—er—unfortunate affair of the night before last has, I suppose, upset all plans, and clapped an effectual stopper on the treasure-hunting scheme, eh?” I asked, turning to the boatswain.

“Oh no, sir, it haven’t,” answered Enderby. “It looked a bit like it, first off, I’ll allow; ’cause, you see, the loss of the Old Man and the mate left us without a navigator, and none of us knew which way to head the ship. But me and Chips, bein’ the only two officers left, had a confab together, and then we mustered the rest of the hands and put it to ’em whether they’d all agree to what we two proposed. And what we proposed was this: Barber had evidently persuaded Cap’n Stenson that there wasn’t no mistake about the treasure actually existin’, and that it might be found, with a bit of tryin’, otherwise the ship wouldn’t be where she is now.

“Then there was the agreement between the two, by which the treasure—when found—was to be equally divided between ’em. Both of ’em havin’ gone over the side, that agreement couldn’t be carried out; but there was Billy, here; and there was us, the crew of the ship; and what me and Chips proposed was, first of all, to get hold of a navigator who’d agree to join in with us, and then go and try to find the treasure; the arrangement bein’ that Billy, as his father’s son, should have half of it, and we—the crew and the navigator—should divide the other half equally between us.

“There was a lot of palaver over it, naturally—you know, sir, what sailor-men are—but at last everybody agreed; and then, since we didn’t know where to head for, we hove-to, waitin’ for something to come along whereby we could get hold of a navigator. Then, at last, along comes you, and you havin’ turned up, I s’pose there’s no reason why we shouldn’t haul down our ensign, swing the head yards, and fill away to complete the v’yage?”

“No,” I said; “no reason at all why you should not do those things. I advise you to fill on the ship at once, and steer as you were heading when you had the misfortune to lose your skipper and mate. Do you know what that course was?”

“Oh yes,” answered Enderby; “the course was north-east, a quarter east.”

“Very good,” said I. “Let that be the course until I shall have had an opportunity to take a set of sights to determine the ship’s position. I suppose Captain Stenson had a sextant, chronometer, and all necessary navigation tables aboard?”

“Yes, sir,” said Billy. “They’re all in his state-room. If you’ll come with me I’ll show them to you.”

“Thanks,” I said. “What I am chiefly interested in, just now, is the chronometer. Do you happen to know when it was last wound, Billy?”

“Yes, sir,” answered the boy; “last Sunday morning. Father used always to wind it every Sunday morning directly after breakfast.”

“Good!” I remarked. “Then everything will be quite all right. And now, bosun, what about berthing me? Where can you stow me?”

“No difficulty at all about that, sir,” answered Enderby. “The Old Man’s state-room is the place for you, because his instruments and charts and books are all in there; and, as of course you’ll want the place to yourself, Billy can shift over into the mate’s state-room, which is also vacant.”

“An excellent suggestion,” I remarked.

“All right,” agreed Enderby; “then we’ll call that settled. Steward!”

And when that functionary appeared the boatswain continued:

“Joe, this is Mr Blackburn, our new skipper. You’ll take your orders from him in future; and—Joe, see that things are straightened up in those two state-rooms, the beds made, and so on.”

The steward very cheerfully assented, and Enderby and the carpenter then rose to go on deck, quickly followed by myself. The two men went for’ard and joined the little crowd assembled on the forecastle, to whom, as I of course surmised, they forthwith proceeded to relate what had passed in the cabin. Whatever it may have been, it seemed to afford the hearers satisfaction, for they smiled and nodded approval from time to time, as the story was being told; and when at length it was ended they all came aft and, while one hand hauled down the ensign and stowed it away, another stationed himself at the wheel, and the remainder tailed on to the braces, swung the headyards, boarded the foretack, and trimmed the jib and staysail sheets, getting way upon the ship and bringing her to her former course; after which, without waiting for any order from me, they set the port topgallant, topmast, and lower studding-sails. This done, the boatswain and carpenter came aft to where I stood and inquired whether what had been done met with my approval; to which I replied in the affirmative.

“And now, sir, about the watches,” remarked Enderby. “Before the night afore last, the mate took the port watch, and I the starboard; but now that the mate’s gone, how would it be if I was to take the port and Chips the starboard watch? Would that suit ye, sir?”

“Yes,” I said, “that would be an excellent arrangement, I think. By the way, how many do you muster in a watch?”

“Four in each, includin’ me and Chips,” answered the boatswain.

“Um! none too many, especially considering the part of the world to which you are bound,” I remarked. “You will have to keep a sharp eye upon the weather, and call me in good time if you should be in the least doubt as to what you ought to do. Has either of you ever been this way before?”

They had not, it appeared.

“And what about your forecastle crowd?” I asked. “Are they all good, reliable men? Some of them are foreigners, aren’t they?”

“Yes,” answered Enderby, lowering his voice and drawing me away from the vicinity of the man at the wheel. “Yes, worse luck, our four A.B.s are all foreigners. Not that I’ve got anything very special to say against ’em. They’re good sailor-men, all of ’em; but the fact is, sir, I don’t like bein’ shipmates with foreigners; I don’t like their ways, and some of ’em has got very nasty tempers. There’s Svorenssen, for instance—that big chap with the red hair and beard—he’s a Roosian Finn; and he’ve got a vile temper, and I believe he’s an unforgivin’ sort of feller, remembers things against a man—if you understand what I mean. Then there’s ‘Dutchy’, as we calls him—that chap that pushed hisself for’ard when we hoisted in your boat—he’s an awk’ard feller to get on with, too; hates bein’ ordered about, and don’t believe in discipline. He and Svorenssen will both be in my watch, and I’ll see to it that they minds their P’s and Q’s. The other two aren’t so bad; but they’d be a lot better if Svorenssen and Dutchy was out of the ship.”

“Ah, well,” I said, “we are five Englishmen to four of them. If they should take it into their heads to be insubordinate I have no doubt we shall know how to deal with them. And now, I should like to have a look at the log-book. I suppose you know where it is kept?”

“Yes,” answered Enderby, “the skipper used to keep it in his cabin. Billy’ll give it you, and show you all you want to see. He knows where his father kept everything. Oh! and I forgot to mention it, but supper’ll be on the table at seven o’clock.”

“Righto!” I returned as I wheeled about and headed for the companion.

Chapter Four.

I take Command of the “Yorkshire Lass.”

“Billy, my boy, where are you?” I called, as I entered the cabin.

“Here I am, sir,” replied the lad, emerging from what had been his father’s state-room. “Is there anything I can do for you, sir?”

Billy Stenson was certainly an amusing and very lovable little chap as he stood there before me, alert and bright-eyed, reminding me somehow of a dog asking for a stick to be thrown into the water, that he may show how cleverly he can retrieve it. If Billy had possessed a tail I am certain that at that moment it would have been wagging vigorously.

“Yes, Billy,” I said. “I should like to see the ship’s log-book. Enderby tells me that you know where it is kept, and can find it for me. And I should like another look at the chart that you showed me a little while ago. Also, if you can put your hand upon that agreement between your father and Mr Barber, I should like to look through it—with any other papers there may be, bearing upon the matter. The story is a very remarkable one, and I feel greatly interested in it.”

“Yes, sir,” said Billy. “I’ll get you the log-book, and the chart, and the agreement. And I think you’d like to see Father’s diary too, sir. When he met Mr Barber, and they began to talk about goin’ huntin’ for the treasure, he started to keep a diary, writin’ down in it everything that Mr Barber told him about it; and there’s a drawin’ in it that Mr Barber made—a sort of picture of the place, showing how it looked, so that they might know it when they saw it again.”

“Ah!” said I. “I should certainly like to see that diary, if you care to show it me. The perusal of it will be most interesting and will probably tell me all that I want to know.”

A few minutes later I was seated at the table, with the chart spread open before me, the log-book open, and the diary at hand, ready for immediate reference. The log-book, however, had nothing to do with the story of the treasure; it simply recorded the daily happenings aboard the brigantine and her position every noon, from the date of her departure from London; and the only interest it had for me was that it enabled me to approximate the position of the ship at the moment of the tragedy. It had been written up to four o’clock in the afternoon of the day on which the tragedy had occurred, while the log slate carried on the story up to midnight. A few minutes sufficed to make me fully acquainted with all that I required to learn from the log-book, and I then laid it aside and turned to the diary.

This document was inscribed in a thick manuscript book, and appeared to have been started about the time when the writer first began seriously to entertain Barber’s proposal to join him in a search for the treasure. It opened with a record of the meeting between Barber and the writer, and set forth at some length the story of Barber’s destitute condition, and what the writer did to ameliorate it. Then followed, in full detail, Barber’s story of his adventure culminating in the discovery of the stranded wreck and the chests of treasure stowed down in her run, with the expression of Barber’s conviction that the ship had been a pirate. It also recorded at length the steps which Barber had taken to obtain the necessary data from which to calculate the latitude of the wreck; and it was the ingenuity of the man’s methods that at last began to impress upon me the conviction that the story might possibly be true, especially as it was illustrated by a sketch—drawn from memory, it is true—showing the appearance of the land from the entrance of the river, very much in the same way that charts are occasionally illustrated for the guidance of the seaman.

This story was succeeded by a record of the successive stages by which the negotiations between the writer and Barber advanced, winding up with a final statement that on such and such a date an agreement had been drawn up in duplicate and signed by the contracting parties, whereby Stenson was to bear the entire cost of the expedition—recouping himself, so far as might be, by securing freights along the route, Barber undertaking to discharge the duties of mate during the voyage, without pay; the proceeds of such treasure as might be found to be equally divided between the two men.

The perusal of the diary fully occupied me right up to the moment when the steward entered to lay the table for supper; and when I had finished it I found myself regarding the adventure with very different eyes from those which I had turned upon it to start with. To be perfectly frank, when I first heard the yarn I had not a particle of faith in the existence of the treasure, and quite set down the late skipper as a credulous fool for risking his hard-earned money in such a hare-brained speculation; but after reading the story as set out in extenso and with a very great wealth of detail, I felt by no means sure that skipper Stenson, very far from being the credulous fool that I had originally supposed him to be, might not prove to have been an exceedingly shrewd and wide-awake person. In a word, I had begun to believe in the truth of the story of the treasure, strange and incredible as it had seemed at first hearing.

And this change of view on my part involved a corresponding change in my attitude toward the adventure. My conversation with Enderby and Johnson over the tea-table had left upon my mind the impression that I had been invited by them, as representatives of the entire crew, to act as navigator and assist in every possible way to secure the treasure, my remuneration for this service to be one share of half the value of the amount of treasure obtained. Now, Barber had expressed the opinion that this value was to be reckoned in millions; but, the eight chests notwithstanding, I regarded this estimate as enormously exaggerated, the result, probably, of ignorance of values on Barber’s part. Nevertheless, assuming the value to be very considerably less, say half a million—and I believed it might possibly amount to that—only a very simple calculation was needed to show that if this sum were divided by two, and one of those parts were awarded to Billy, as skipper Stenson’s heir, the remaining sum of one quarter of a million divided into eleven equal parts—there being eleven prospective participants, including myself—would yield to each participant nearly twenty-three thousand pounds; a sum very well worth trying for. Viewing the matter in all its bearings I finally came to the conclusion that, regarding it merely as a speculation, it might be quite worth my while to throw in my lot with these men.

The project certainly had its allurements, for it must be remembered that I was then young enough to be thoroughly imbued with the spirit of adventure. I was poor, and even the bare possibility of making over twenty thousand pounds in a few months very powerfully appealed to me; and finally, if I rejected this chance and made the best of my way back home, there was the possibility that I might be out of employment for a considerable period, while at best I could hope for nothing better than another billet as fourth officer in a Planet boat. In fine, the more I considered the boatswain’s proposal, the better I liked it; but at the same time some inward monitor whispered that it would be wise not to manifest too keen a readiness to fall in with the men’s proposals.

While these reflections were passing through my mind I noticed that the steward, in laying the table for supper, was laying for one person only—myself. But while this arrangement had its advantages, it also had certain disadvantages which I regarded as outweighing the former. I therefore bade him lay for the boatswain and the carpenter as well; for I had sense enough to recognise the importance of keeping my finger upon the pulse of the crew, so to speak, and I knew that this could best be done by means of little confidential chats with the boatswain and Chips, who were the men’s representatives.

The steward presently brought along from the galley the chief ingredients of the supper, consisting of a pot of piping hot cocoa and a dish of steaming “lobscouse”, to be followed, he informed me, by a jam tart. Then I sent Billy up on deck to find Enderby and bid him come to supper in the cabin.

During the progress of the meal the conversation was of a general character, consisting chiefly of discussions concerning the weather, the behaviour of the ship under various circumstances, and the relation of certain not very interesting incidents connected with the voyage. But after we had finished, and Chips had come down to take his supper while Enderby took over the charge of the deck, the boatswain fell into step alongside me as I paced fore and aft, enjoying the unwonted luxury of a pipe.

“There’s just one p’int in what was said at tea-time, Mr Blackburn,” he remarked, “that I feels a bit hazy about, and that I haven’t been able to make quite clear to the men. You remember that when I spoke about you navigatin’ the ship for us, you said you’d be willin’ to do it so far as the nearest port. That’s about what it was, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” I replied. “That is what I said.”

“So I thought,” concurred the boatswain. “Well, sir,” he continued, “do that mean that you’re unwillin’ to take a hand in this here treasure-huntin’ game with us?”

“Oh, as to that,” I said, “I really have not had time to consider the matter, as yet. Besides, I do not quite know what it is that you men propose. Let me know that, and I will give the matter my most careful consideration.”

“Ay, ay, yes, of course; that’s quite right,” agreed Enderby. “I’ll have a talk to the chaps for’ard, and hear what they’ve got to say about it. And—about that ‘nearest port’ that you mentioned, sir, had ye got any particular port in your mind’s eye?”

“N–o, I can scarcely say that I had,” I returned—“or if I had, it was probably Port Louis, Mauritius. But all my ideas are very hazy thus far, you must understand, for at the present moment I do not know where the ship is, and I shall be unable to discover her position until I can take the requisite sights. Then we will have out the chart, prick off our position, and discuss the matter further.”

“Yes, sir; thank ’e,” answered Enderby. “And that’ll be some time to-morrow, I s’pose?”

“Certainly,” I agreed; “some time to-morrow—unless of course the sky should be obscured by cloud, preventing the taking of the necessary observations. But I think we need not seriously fear anything of that kind.”

“No, sir, no; not much fear of that,” agreed Enderby; and therewith he trundled away for’ard and joined a little group of men who seemed to be somewhat impatiently awaiting him.

It was a pleasant evening. The sun was on the point of setting, and the western sky was a magnificent picture of massed clouds ablaze with the most brilliant hues of gold, scarlet, crimson, and purple, while the zenith was a vast dome of purest, richest ultramarine. A fresh breeze was blowing steadily out from about west-sou’-west, and there was a long and rather high swell, overrun by seas just heavy enough to break in squadrons of creaming foam-caps that would have meant an anxious night for me had I still been adrift in the life-boat. Apart from those white foam-caps the ocean was a wide expanse of deepest sapphire blue, over which the brigantine was rolling and plunging at a speed of fully eight knots, her taut rigging humming like an Aeolian harp with the sweep of the wind through it. For several minutes after Enderby had left me I stood gazing in admiration at the brilliant, exhilarating scene; then, for the mere pleasure of stretching my legs a bit, after being for so long cramped within the confined limits of the life-boat, I started upon a vigorous tramp fore and aft the weather side of the deck, between the wheel grating and the main rigging.