The Project Gutenberg EBook of Absurd Ditties, by G. E. Farrow

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Absurd Ditties

Author: G. E. Farrow

Illustrator: John Hassall

Release Date: October 1, 2016 [EBook #53190]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ABSURD DITTIES ***

Produced by David Edwards, readbueno and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Books project.)

TO

MY FRIEND

T. FRANCIS VERE FOSTER.

G. E. F.

BY

G. E. FARROW

Author of "The Wallypug of Why" etc.

WITH PICTORIAL ABSURDITIES

BY

JOHN HASSALL

LONDON

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, Ltd.

New York: E. P. Dutton and Co.

1903

| |

|

PAGE. |

| |

| I. |

THAT OF MR. JUSTICE DEAR |

1 |

| |

| II. |

THAT OF THE LATE MR. BROWN |

5 |

| |

| III. |

THAT OF OUR OLD FRIEND, BISHOP P. |

9 |

| |

| IV. |

THAT OF CAPTAIN ARCHIBALD MCKAN |

15 |

| |

| V. |

THAT OF MATILDA |

20 |

| |

| VI. |

THAT OF "DOCTHOR" PATRICK O'DOOLEY |

25 |

| |

| VII. |

THAT OF MY AUNT BETSY |

31 |

| |

| VIII. |

THAT OF THE TUCK-SHOP WOMAN |

37 |

| |

| IX. |

THAT OF S. P. IDERS WEBBE, SOLICITOR |

43 |

| |

| X. |

THAT OF MONSIEUR ALPHONSE VERT |

50 |

| |

| XI. |

THAT OF LORD WILLIAM OF PURLEIGH |

55 |

| |

| XII. |

THAT OF PASHA ABDULLA BEY |

60 |

| |

| XIII. |

THAT OF ALGERNON CROKER |

65 |

| |

| XIV. |

THAT OF——? |

69 |

| |

| XV. |

THAT OF THE RIVAL HAIRDRESSERS |

75 |

| |

| XVI. |

THAT OF THE AUCTIONEER'S DREAM |

80 |

| |

| XVII. |

THAT OF THE PLAIN COOK |

86 |

| |

| XVIII. |

THAT OF TWO MEDDLESOME PARTIES AND THEIR RESPECTIVE FATES |

91 |

| |

| XIX. |

THAT OF THE HOOLIGAN AND THE PHILANTHROPIST |

98 |

| |

| XX. |

THAT OF THE SOCIALIST AND THE EARL |

104 |

| |

| XXI. |

THAT OF THE RETIRED PORK-BUTCHER AND THE SPOOK |

109 |

| |

| XXII. |

THAT OF THE POET AND THE BUCCANEERS |

115 |

| |

| XXIII. |

THAT OF THE UNDERGROUND "SULPHUR CURE" |

121 |

| |

| XXIV. |

THAT OF THE FAIRY GRANDMOTHER AND THE COMPANY PROMOTER |

127 |

| |

| XXV. |

THAT OF THE GEISHA AND THE JAPANESE WARRIOR |

132 |

| |

| XXVI. |

THAT OF THE INDISCREET HEN AND THE RESOURCEFUL ROOSTER |

137 |

| |

| XXVII. |

THAT OF A DUEL IN FRANCE |

141 |

| |

| XXVIII. |

THAT OF THE ASTUTE NOVELIST |

146 |

| |

| XXIX. |

THAT OF THE ABSENT-MINDED LADY |

151 |

| |

| XXX. |

THAT OF THE GERMAN BAKER AND THE COOK |

155 |

| |

| XXXI. |

THAT OF THE CONVERTED CANNIBALS |

160 |

| |

| XXXII. |

THAT OF A FRUITLESS ENDEAVOUR |

164 |

| |

| XXXIII. |

THAT OF THE UNFORTUNATE LOVER |

168 |

| |

| XXXIV. |

THAT OF THE FEMALE GORILLY |

174 |

| |

| XXXV. |

THAT OF THE ARTIST AND THE MOTOR-CAR. (A TRAGEDY) |

179 |

| |

| XXXVI. |

THAT OF THE INCONSIDERATE NABOB AND THE LADY WHO DESIRED TO BE A BEGUM |

184 |

| |

| XXXVII. |

THAT OF DR. FARLEY, M.D., SPECIALIST IN LITTLE TOES |

188 |

| |

| XXXVIII. |

THAT OF JEREMIAH SCOLES, MISER |

192 |

| |

| XXXIX. |

THAT OF THE HIGH-SOULED YOUTH |

196 |

| |

| LX. |

THAT OF MR. JUSTICE DEAR'S LITTLE JOKE AND THE UNFORTUNATE MAN WHO COULD NOT SEE IT |

201 |

| |

| LXI. |

THAT OF THE LADIES OF ASCENSION ISLAND |

205 |

| |

| LXII. |

THAT OF THE ARTICULATING SKELETON |

208 |

| |

| LXIII. |

THAT OF YE LOVE PHILTRE: (AN OLD-ENGLISH LEGEND) |

211 |

| |

| LXIV. |

THAT OF THE BARGAIN SALE |

216 |

| |

| LXV. |

THAT OF A DECEASED FLY (A BALLADE) |

221 |

| |

| |

EPILOGUE |

224 |

I.

THAT OF MR. JUSTICE DEAR.

"'Tis really very, very queer!"

Ejaculated Justice Dear,

"That, day by day, I'm sitting here

Without a single 'case.'

This is the twenty-second pair

Of white kid gloves, I do declare,

I've had this month. I can not wear

White kids at such a pace."

His Lordship thought the matter o'er.

"Crimes ne'er have been so few before;

Not long ago, I heard a score

Of charges every day;

And now—dear me! how can it be?—

And, pondering thus, went home to tea.

(He lives Bayswater way.)

A frugal mind has Justice Dear

(Indeed, I've heard folks call him "near"),

And, caring naught for jibe or jeer,

He rides home on a bus.

It singularly came to pass,

This day, he chanced to ride, alas!

Beside two of the burglar class;

And one addressed him thus:

"We knows yer, Mr. Justice Dear,

You've often giv' us 'time'—d'ye hear?—

And now your pitch we're going to queer,

We criminals has struck!

We're on the 'honest livin' tack,

An' not another crib we'll crack,

So Justices will get the sack!

How's that, my legal buck?"

This gave his Lordship quite a fright,

He had not viewed it in that light.

"Dear me!" he thought, "these men are right,

I'd better smooth them down.

"Let's not fall out, my friends," said he,

"Continue with your burglarie;

Your point of view I clearly see.

Ahem! Here's half-a-crown."

The morning sun shone bright and clear

On angry Mr. Justice Dear;

His language was not good to hear;

With rage he'd like to burst.

His watch and chain, and several rings,

His silver-plate, and other things,

Had disappeared on magic wings—

They'd burgled his house first!

II.

THAT OF THE LATE MR. BROWN.

Life has its little ups, and downs,

As has been very truly said,

And Mr. Brown,

Of Camden Town

(Alas! the gentleman is dead),

Found out how quickly Fortune's smile

May turn to Fortune's frown;

And how a sudden rise in life

May bring a person down.

He lived—as I remarked before—

Within a highly genteel square

At Camden Town,

Did Mr. Brown

(He had been born and brought up there);

But—waxing richer year by year—

Grew prosperous and fat,

And left the square at Camden Town

To take a West End flat.

It was a very stylish flat,

With such appointments on each floor

As Mr. Brown

At Camden Town

Had never, never seen before:

Electric lights; hydraulic lifts,

To take one up and down;

And telephones to everywhere.

(These quite bewildered Brown.)

The elevator pleased him most;

To ride in it was perfect bliss.

"I say!" cried Brown,

"At Camden Town

We'd nothing half as good as this."

From early morn till dewy eve

He spent his time—did Brown—

In being elevated up,

And elevated down.

One night—I cannot tell you why—

When all the household soundly slept,

Poor Mr. Brown

(Late Camden Town)

Into the elevator stept;

It stuck midway 'twixt floor and floor,

And when they got it down,

They found that it was all U.—P.

With suffocated Brown.

Yes, life

is full of ups and downs,

As someone said in days of yore.

They buried Brown

At Camden Town

(The place where he had lived before);

And now, alas! a-lack-a-day!

In black and solemn gowns,

Disconsolate walk Mrs. Brown

And all the little Browns.

III.

THAT OF OUR OLD FRIEND BISHOP P.

(With many thanks to Mr. W. S. Gilbert for his kind assurances

that the inclusion of these verses causes him no offence.)

Twice Mr. Gilbert sang to you

Of Bishop P., of Rum-ti-foo;

Now, by your leave, I'll do that too,

Altho' I'm bound to fail

(So you will tell me to my face)

In catching e'en the slightest trace

Of true Gilbertian charm, or grace,

To decorate my tale.

Still, I will tell, as best I can,

How Bishop Peter—worthy man—

Is getting on by now.

Now where shall I begin? Let's see?

You know, I think, that Bishop P.

(Wishful to please his flock was he)

Once took the bridegroom's vow.

You doubtless recollect, His Grace

Wed Piccadil'lee of that place,

And Peterkins were born apace,

When she became his bride.

In fact I'm told that there were three,

When dusky Piccadillillee,

In odour of sanctittittee,

Incontinently died.

Some years have passed since her demise

But Bishop Peter—bless his eyes—

That saintly prelate, kind, and wise,

Is excellently well.

And, not so very long ago,

He sought to wed—this gallant beau

(His faithful flock desired it so)—

Another Island belle.

There was one difficulty, this:

Our Peter wooed a dusky Miss

Who (tho' inclined to married bliss)

Declared him rather old;

Who giggled at his bald, bald head,

And even went so far, 'tis said,

As to decline His Grace to wed,

Did Lollipoppee bold.

But, one day, on that far-off reef,

A merchant vessel came to grief,

And all the cargo—to be brief—

Was washed upon the shore.

Most of the crew, I grieve to state,

Except the Bos'un and the Mate,

Were lost. Theirs was a woesome fate,

And one we all deplore.

Amongst the wreckage on the strand,

A box of "Tatcho" came to land,

Which, there half buried in the sand,

The Bishop—singing hymns

Amongst his flock down by the shore—

Discovered, and they open tore

The case. Behold! The contents bore

The magic name of Sims.

"What! G. R. Sims?" quoth Bishop P.

(Visions of "Billy's Rose" had he),

"Good gracious now! It Sims to me

I've heard that name before."

(Oh, well bred flock! there was not one

Who did not laugh at this poor pun;

They revelled in their Bishop's fun.

They even cried "Encore!")

Then spake the Mate (whose name was Ted):

"Now this 'ere stuff, so I've 'eard said,

Will make the 'air grow on yer 'ead

As thick as any mat."

"Indeed?" quoth worthy Bishop P.;

"Then 'tis the very thing for me,

For I am bald, as you may see."

His Grace removed his hat.

The Bo'sun quickly broke the neck

Of one large bottle from the wreck,

Proceeding then His Grace to deck

With towels (careful man,

This was to save his coat of black,

For "Tatcho" running down one's back

Is clearly off its proper tack).

And then the fun began.

For Ted he rubbed the liquid through,

As hard as ever he could do.

And worthy Jack rubbed some in too

(The Bo'sun's name was Jack).

And day by day they did the same.

Now "Tatcho" ne'er belies its fame,

And soon a little hair there came

(His Lordship's hair is black).

Miss Lollipoppee views with glee

The change in worthy Bishop P.

Now quite agreed to wed is she

(The banns were called to-day).

No "just cause or impediment"

Can interfere with their content;

The natives' loyal sentiment

Is summed up in "Hooray!"

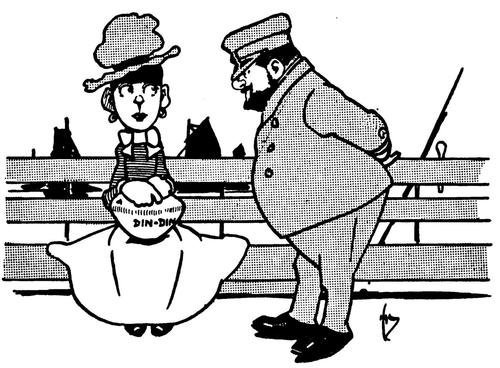

IV.

THAT OF CAPTAIN ARCHIBALD McKAN.

There never lived a worthier man

Than Captain Archibald McKan.

I knew him well some time ago

(I speak of twenty years or so);

Sans peur et sans reproche was he;

He was the soul of chivalry,

Was Captain Archibald McKan.

True greatness showed in all his mien,

No haughty pride in him was seen,

Though, captain of a steamer, he,

From Greenwich unto far Chelsea,

That, spite of weather, wind, and tide,

From early Spring to Autumn plied,

Brave, modest Captain A. McKan.

However sternly might his roar

Reverberate from shore to shore

Of "Ease her! Back her! Hard astern!"

His duty done, with smile he'd turn

And be most affable and mild

To every woman, man, or child

Aboard, would Captain A. McKan.

He reassured the anxious fears

Of nervous ladies—pretty dears!—

He in his pocket carried toys

And sweets for little girls and boys;

He talked in quite familiar way

With men who voyaged day by day,

Did Captain Archibald McKan.

In fact, as I've already said,

No man alive—or even dead—

Was freer from reproach than he;

And yet of Fortune's irony

(Though such a very decent sort)

This worthy man was e'en the sport.

Alas! was Captain A. McKan!

"Cherchez la femme." The phrase is trite,

Yet here, as usual, 'twas right.

Our Captain noted every day

A certain girl rode all the way

From Greenwich Pier to Wapping Stair.

"It cannot be to take the air,"

Thought Captain Archibald McKan.

She calmly sat, with downcast eye;

And looking both demure and shy;

Yet, once, he caught a roving glance,

Which made his pulses wildly dance;

And,—though as modest as could be—

"I do believe she's gone on me,"

Considered Captain A. McKan.

"Why else should she persistently

Select my boat alone?" thought he;

"I wonder why she comes? I'll ask,

Though 'tis a very ticklish task."

So, walking forward with a smile,

Beside the lass he stood awhile,

Then coughed, did Captain A. McKan.

"You're frequently aboard my boat,"

Began he; "she's the best afloat;

But, pray, may I enquire, do you

So very much admire the view?"

"Er—moderately, sir," said she.

"Exactly so! It must be me!"

Decided Captain A. McKan.

"Come, tell me, Miss, now no one's by,"

He whispered; "Won't you tell me why

You come so oft? There's naught to dread."

The lady looked surprised, and said:

"My husband works at Wapping Stair,

I daily take his dinner there."

Poor Captain Archibald McKan!

Yes, I love you, dear Matilda,

But you may not be my bride,

And the obstacles are many

Which have caused me to decide.

Firstly, what is most annoying,

And I'm not above confessing,

Is, that I think you indolent,

And over-fond of dressing.

I've known you spend an hour or two

In a-sitting on a chair,

And a-fussing and attending

To your toilet or your hair.

There's another little matter—

You may say a simple thing—

Yet, Matilda, I must own it,

I object to hear you sing.

For the sounds you make in singing

Are so very much like squalling,

That the only term appropriate

To them is caterwauling.

Indeed, I've never heard such horrid

Noises in my life,

And I'd certainly not tolerate

Such singing in a wife.

And, Matilda dear, your language!

It is really very bad;

The expressions which you use at times,

They make me feel quite sad.

It is very, very shocking,

But I do not mind declaring

That I've heard some sounds proceeding

From your lips so much like swearing,

That I've had to raise a finger,

And to close at least one ear,

For I couldn't feel quite certain

What bad words I mightn't hear.

But worse than this, Matilda:

I hear, with pious grief,

Many rumours that Matilda

Is no better than a thief

And I'm shocked to find my darling

So entirely lost to feeling,

As to go and give her mind up

Unto picking and a-stealing.

Oh, Matilda! pray take warning,

For a prison cell doth yearn

For a person that appropriates

And takes what isn't her'n.

And the culminating blow is this:

You stay out late at night.

Now, Matilda dear, you must confess

To do this is not right.

Where you go to, dear, or what you do,

There really is no telling,

And with rage and indignation

My fond foolish heart is swelling.

Yet the faults which I've enumera-

Ted can't be wondered at,

When one realises clearly

That "Matilda"—is a cat.

VI.

THAT OF "DOCTHOR" PATRICK O'DOOLEY.

In the South Pacific Ocean

In an oiland called Koodoo,

An' the monarch ov thot oiland

Iz King Hulla-bulla-loo.

Oi wuz docthor to thot monarch

Wonct. Me name iz Pat O'Dooley.

Yis, you're roight. Oi come from Oirland,

From the County Ballyhooly.

An' Oi'll tell yez how Oi came to be

A docthor in Koodoo;

May the Divil burn the ind ov me,

If ivery word's not thrue.

Oi wuz sailin' to Ameriky,

Aboard the "Hilly Haully,"

Which wuz drounded in the ocean,

For the toime ov year wuz squally.

An' Oi floated on a raft, sor,

For some twinty days or more,

Till Oi cum to Koodoo Island,

Phwich Oi'd niver seen before.

But the natives ov thot counthry,

Sure, would take a lot ov batin',

For a foine young sthrappin' feller

They think moighty pleasint atin'.

An' they wint an' told the King, sor,

Him called Hulla-bulla-loo.

"Ye come from Oirland, sor?" sez he.

"Bedad!" sez Oi, "thot's true."

Thin he whispered to the cook, sor;

An' the cook he giv me warnin':

"It's Oirish stew you'll be," sez he,

"To-morrow, come the marnin'."

But to-morrow, be the Powers, sor,

The King wuz moighty bad,

Wid most odjus pains insoide him,

An' they nearly drove him mad;

So he sint a little note, sor,

By the cook, apologoizin'

For not cooking me that day, sor,

Wid politeness most surprisin'!

An' Oi wrote him back a letther,

Jist expressin' my regret,

Thot Oi shouldn't hiv the honor,

Sor, ov bein' cooked an' et;

An' Oi indid up the letther

Wid a midical expresshin,

As would lead him to imagine

Oi belonged to the professhin.

Och! he sint for me

at wonct, sor.

"If ye'll only save me loife,"

Sez he, "Oi'll give yez money,

An' a most attractive woife,

An' ye won't be in the menu

Ov me little dinner party

If ye'll only pull me round," sez he,

"An' make me sthrong an' hearty."

So Oi made a diagnosis

Wid my penknife an' some sthring

(Though Oi hadn't got a notion

How they made the blessid thing;

But Oi knew thot docthors did it

Phwen they undertook a case, sor),

An' Oi saw his pulse, an' filt his tongue,

An' pulled a sarious face, sor.

Thin Oi troied a bit ov blarney.

"Plaze, yer gracious Madjisty,

It's yer brains iz much too big, sor,

For yer cranium, ye see."

But the King he looked suspicious,

An' he giv a moighty frown, sor.

"The pain's not there at all," sez he,

"The pain is further down, sor."

"Oi'm commin', sor, to thot," sez Oi.

"Lie quiet, sor, an' still,

While Oi go an' make yer Madjisty

Me cilebratid pill."

In the pocket ov me jacket

Oi had found an old ship's biscuit

("An' Oi think," sez Oi, "'twill do," sez Oi,

"At any rate Oi'll risk it").

The biscuit it wuz soft an' black

By raisin ov the wet,

An' it made the foinist pill, sor,

Thot Oi've iver seen as yet;

It wuz flavoured rayther sthrongly

Wid salt wather an' tobaccy,

But, be jabers, sor, it did the thrick,

An' cured the blissid blackie!

The King wuz as deloighted,

An' as grateful as could be,

An' he got devorced from all his woives,

An' giv the lot to me;

But a steamer, passin' handy,

Wuz more plazin' to "yours trooly,"

An' among the passingers aboard

Wuz the "Docthor",—Pat O'Dooley.

VII.

THAT OF MY AUNT BETSY.

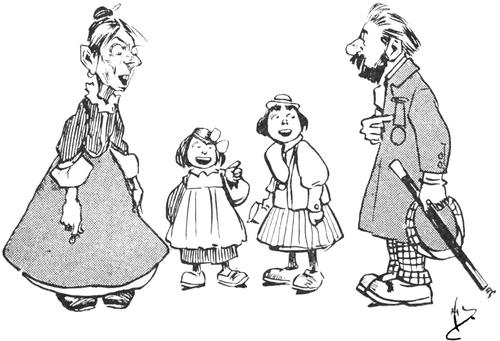

You may have met, when walking out

or thereabout,

A lady (angular and plain)

Escorted by an ancient swain,

Or, possibly, by two,

Each leading by a piece of string

A lazy, fat, and pampered thing

Supposed to be a dog. You may,

Perhaps, have noticed them, I say,

And, if so, thought, "They do

Present unto the public gaze

A singular appearance—very."

That lady, doubtless, was my aunt,

Miss Betsy Jane Priscilla Perry.

The gentleman—or gentle

men—

Attending her were Captain Venne

And Major Alec Stubbs. These two

For many years had sought to woo

My maiden aunt, Miss P.,

Who never could make up her mind

Which one to marry, so was kind

To one or other—each in turn—

Thus causing jealous pangs to burn.

I incidentally

Should mention here the quadrupeds—

Respectively called "Popsey Petsey,"—

A mongrel pug;—and "Baby Heart,"—

A poodle—both belonged to Betsy.

You'd notice Captain Venne was tall,

And Major Stubbs compact and small;

These two on nought could e'er agree,

Except in this—they hated me,

Sole nephew to Aunt Bess.

My aunt was very wealthy, and

I think you'll quickly understand

The situation, when I say

That Captain Venne was on half-pay,

And Major Stubbs on less.

To me it was so very plain

And evident, I thought it funny

My aunt should never, never see

They wanted, not her, but her money.

And Stubbs and Venne they did arrange

A plan, intended to estrange

My aunt and me. They told her lies;

And one day, to my great surprise,

A letter came for me.

Requesting me to "call at six,"

For aunt had "heard of all the tricks

I had been up to," and "was sad

At hearing an account so bad."

I went—in time for tea.

My aunt was looking so severe

I felt confused, a perfect noodle

While Major Stubbs caressed the pug,

And Captain Venne he nursed the poodle.

"Dear Major Stubbs," my aunt began,

"Has told me all—quite all he can—

Of your sad goings on. Oh, fie!

Where will you go to when you die,

You naughty wicked boy?"

And Captain Venne has told me too

What very dreadful things you do.

Of course I cannot but believe

My two dear friends. They'd not deceive,

Nor characters destroy,

Without a cause. Go, leave me now,

You'll see my purpose shall not falter

I'll send at once for Lawyer Slymm,

My latest will to bring and alter."

I fear I lost my temper—quite;

I know I said what wasn't right;

You see, I felt it hard to bear

(And really, I contend, unfair),

To be misjudged like this.

I tried to argue, but 'twas vain,

"My mind is fixed—my way is plain,"

My aunt declared. "Then hear me now!"

I hotly cried, "There's naught, I vow,

To cause you to dismiss

Your nephew thus, but, as you please.

And if, perchance, you wish to do it,

Your money leave to your two friends;

They want it, and—they're welcome to it."

I hurried out. I slammed the door.

I vowed I'd never call there more.

And neither did I, in my pride,

Till six weeks since, when poor aunt died,

And then, from Lawyer Slymm

I got a little note, which said:

"The will on Tuesday will be read."

I went, and found that "Baby Heart"

From Captain Venne must ne'er depart—

She had been left to him;

While "Popsey Petsey" Major Stubbs

Received as his sole legacy

And that was all. The money—oh!

The money—that was left to me.

VIII.

THAT OF THE TUCK-SHOP WOMAN.

Of all the schools throughout the land

St. Vedast's is the oldest, and

All men are proud

(And justly proud)

Who claim St. Vedast's as their Al-

Ma mater. There I went a cal-

Low youth. Don't think I'm going to paint

The glories of this school—I ain't.

The Rev. Cecil Rowe, M.A.,

Was classics Master in my day,

A learned man

(A worthy man)

In fact you'd very rarely see

A much more clever man than he.

But if you think you'll hear a lot

About this person,—you will not.

The porter was a man named Clarke;

We boys considered it a lark

To play him tricks

(The usual tricks

Boys play at public schools like this),

And Clarke would sometimes take amiss

These tricks. But don't think I would go

And only sing of him. Oh, no!

This ditty, I would beg to state,

Professes likewise to relate

The latter words

(The solemn words)

Of her who kept the tuck-shop at

St. Vedast's. I'd inform you that

The porter was her only son

(The reason was—she had but one).

For many years the worthy soul

Had kept the shop—the well-loved goal

Of little boys

(And larger boys)

Who bought the tarts, and ginger pop

And other things sold at her shop—

But, feebler growing year by year,

She felt her end was drawing near.

She therefore bade her son attend,

That she might whisper, ere her end,

A startling tale

(A secret tale)

That on her happiness had preyed,

And heavy on her conscience weighed

For many a year. "Alas! my son,"

She sighed, "injustice has been done.

"Let not your bitter anger rise,

Nor gaze with sad reproachful eyes

On one who's been

(You know I've been)

For many years your mother, dear;

And though you think my story queer,

Believe—or I shall feel distressed—

I thought I acted for the best.

"When you were but a tiny boy

(Your mother's and your father's joy),

Good Mr. Rowe

(The Revd. Rowe)

Was but a little baby too,

Who very much resembled you,

And, being poorly off in purse,

I took this baby out to nurse.

"Alike in features and in size—

So like, indeed, the keenest eyes

Would find it hard

(Extremely hard)

To tell the t'other from the one——"

"Hold! though your tale is but begun,"

The porter cried, "a man may guess

The secret of your keen distress.

"You changed the babes at nurse, and I

(No wonder that you weep and sigh),

Tho' callèd Clarke

(School Porter Clarke),

Am really Mr. Rowe. I see.

And he, of course, poor man, is me,

While all the fortune he has known

Through these long years should be my own.

"Oh falsely, falsely, have you done

To call me all this time your son;

I've always felt

(Distinctly felt)

That I was born to better things

Than portering, and such-like, brings,

I'll hurry now, and tell poor Rowe

What, doubtless, he will feel a blow."

"Stay! stay!" the woman cried, "'tis true,

My poor ill-treated boy, that you

Have every right

(Undoubted right)

To feel aggrieved. I had the chance

Your future welfare to advance

By changing babes. I knew I'd rue it,

My poor boy—but—I didn't do it."

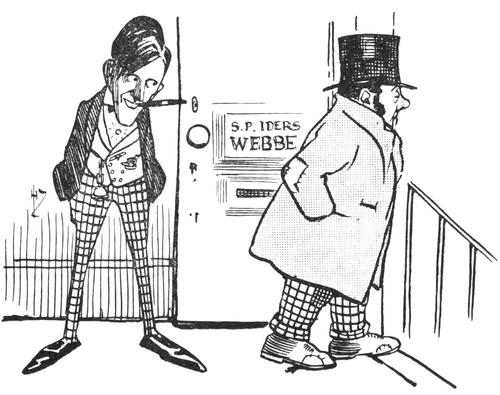

IX.

THAT OF S. P. IDERS WEBBE, SOLICITOR.

Young Mr. S. P. Iders Webbe,

Solicitor, of Clifford's Inn,

Sat working in his chambers, which

Were far removed from traffic's din.

To those in legal trouble he

Lent ready ear of sympathy—

And six-and-eightpence was his fee.

To widows and to orphans, too,

Young Mr. Webbe was very nice,

And turned none from his door away

Who came to seek for his advice:

To these, I humbly beg to state—

The sad and the disconsolate—

His fee was merely six-and-eight.

He'd heave a sympathetic sigh,

And squeeze each bankrupt client's hand

While listening to a tale of woe

Salt tears within his eyes would stand.

Naught, naught his sympathies could stem,

And he would only charge—ahem!—

A paltry six-and-eight to them.

This gentleman, as I observed,

Was calmly seated at his work,

When, from the waiting-room, a card

Was brought in by the junior clerk.

"Nathaniel Blobbs? Pray ask him to

Step in," said Webbe. "How do you do?

A very pleasant day to you."

"A pleasant day be hanged!" said Blobbs,

A wealthy man and very stout

(That he was boiling o'er with rage

There could not be the slightest doubt).

"I'm given, sir, to understand

You're suitor for my daughter's hand.

An explanation I demand!

"I know your lawyer's tricks, my man;

In courting of my daughter Jane—

Who's rather plain and not too young—

My money's what you seek to gain.

Confound you, sir!" the man did roar.

"My daughter Jane is no match for

A beggarly solicitor!"

At words like these most gentlemen

Would really have been somewhat riled;

But do not think that Mr. Webbe

Was angry. No; he merely smiled.

But, oh! my friends, the legal smile

Is not to trust. 'Tis full of guile.

(So smiles the hungry crocodile.)

"I see," Webbe most politely said,

"My worthy sir, your point of view.

You're wealthy; I am poor. Of course,

What I proposed would never do.

If only, now, I'd property,

And you were—well, as poor as me——"

"Pooh! that," cried Blobbs, "can never be."

"Think not?" said Webbe. "Well, p'r'aps you're right.

And so—there's nothing more to say.

You must be going? What! so soon?

I'm sorry, sir, you cannot stay!"

Blobbs went—and slammed the outer door.

Webbe calmly made the bill out for

The interview—a lengthy score.

He charged—at highest legal rate—

For every word he'd uttered; and

He even put down six-and-eight

"To asking for Miss Blobbs's hand";

Next, in the Court of Common Pleas

A "Breach of Promise" case, with ease,

He instituted—if you please.

He gained the day, because the maid

Was over age, the Judge averred,

And Blobbs was forced to "grin and pay,"

Although he vowed 'twas most absurd.

The "damages," of course, were slight;

But "legal costs" by no means light.

(Webbe shared in these as was his right.)

Outside the Court indignant Blobbs

Gave vent to some expressions which

Were libellous, and quickly Webbe

Was "down on him" for "using sich."

Once more the day was Webbe's, and he,

By posing as a damagee,

Obtained a thousand pounds, you see.

With this round sum he then contrived

To buy a vacant small estate

Adjoining Blobbs, who went and did

Something illegal with a gate.

Webbe "had him up" for that, of course;

Then something else (about a horse),

And later on a water-course.

He sued for this, he sued for that,

Till action upon action lay,

And in the Royal Courts of Law

"Webbe versus Blobbs" came on each day.

"Law costs" and big "retaining fees,"

"Mulcted in fines"—such things as these

Made Blobbs feel very ill at ease.

As Webbe grew rich, so he grew poor,

Till finally he said: "Hang pride!

I'll let this fellow, if he must,

Have Jane, my daughter, for his bride."

He went once more to Clifford's Inn.

Webbe welcomed him with genial grin:

"My very dear sir, pray step in."

"Look here!" cried Blobbs. "I'll fight no more!

You lawyer fellows, on my life,

Will have your way. I must give in.

My daughter Jane shall be your wife!"

"Dear me! this is unfortunate,"

Said Webbe. "I much regret to state

Your condescension comes too late.

"For, sir, I marry this day week

(Being a man of property)

The young and lovely daughter of

Sir Simon Upperten, M.P."

Then, in a light and airy way:

"I think there's nothing more to say.

Pray, mind the bottom step. Good day!"

X.

THAT OF MONSIEUR ALPHONSE VERT.

Your Mistair Rudyar' Kipling say

Ze cricquette man is "flannel fool."

Ah! oui! Très bon! I say so too,

Since Mastair Jack, enfant at school,

He show me how to play ze same.

I like it not—ze cricquette game.

My name is Monsieur Alphonse Vert

(You call him in ze English "Green");

I go to learn ze English tongue,

And lodge myself at Ealing Dean

In family of Mistair Brown,

Who has affaire each day "in town."

Miss Angelina Brown she is

Très charmante—what you call "so pretty";

I walk and talk wiz her sometimes

When Mr. Brown go to ze City;

I fall in love (pardon zese tears)

All over head, all over ears.

I buy her books, and flowers (

bouquet),

And tickets for la matinée,

And to ze cricquette match we go,

Hélas! upon one Saturday.

To me she speak zere not at all.

But watch ze men, and watch ze ball.

Ze cricquette men zey run, zey bat,

Zey throw ze ball, zey catch, zey shout;

And Angelina clap her hands.

Vot for, I know not, all about,

And in myself I say "Ah! oui!

I too a cricquette man shall be."

To Angelina's brother Jack

(His name is also Mastair Brown)

I say, "Come, teach me cricquette match,

And I will give you half-a-crown."

Jack say, "My eye!" (in French

mes yeux)

[1]"Oh! what a treat!" (in French c'est beau).

After, to Ealing Common we

Go out, with "wicquette" and with "ball,"

And what Jack calls a "cricquette-bat."

(Zese tings I do not know at all;

But Angelina I would catch,

So "Allons! Vive la cricquette match!")

I hold ze "bat," Jack hold ze "ball."

"Now zen! Look out!" I hear him cry.

I drop ze "bat," I look about;

Ze ball—he hit me in ze eye."

I cry, "Parbleu!" Ze stars I see.

I think it is "all up" wiz me.

I try again. Ze "ball" is hard.

I catch him two times—on ze nose.

I run, I fall, I hurt my arm,

I spoil my new white flannel clothes,

In every part I'm bruised and sore,

So cricquette match I play no more.

I change my clothes, I patch my eye,

I tie my nose up in a sling,

And to Miss Angelina Brown

Myself and all my woes I bring.

"Ah, see," I cry, "how love can make

Alphonse a hero for thy sake."

But Angelina laugh and laugh,

And say, "I know it isn't right

To laugh; but you must please forgive

Me. You look such a fright!"

And next day Jack say, "I say, Bones,

My sister's going to marry Jones."

XI.

THAT OF LORD WILLIAM OF PURLEIGH.

Lord William of Purleigh retired for the night

With a mind full of worry and trouble,

Which was caused by an income uncommonly slight,

And expenses uncommonly double.

Now the same sort of thing often happens, to me—

And perhaps to yourself—for most singularlee

One's accounts—if one keeps 'em—will never come right,

If, of "moneys received," one spends double.

His lordship had gone rather early to bed,

And for several hours had been sleeping,

When he suddenly woke—and the hair on his head

Slowly rose—he could hear someone creeping

About in his room, in the dead of the night,

With a lantern, which showed but a glimmer of light,

And his impulse, at first, was to cover his head

When he heard that there burglar a-creeping.

But presently thinking "Poor fellow, there's naught

In the house worth a burglar a-taking,

And, being a kind-hearted lord, p'r'aps I ought,

To explain the mistake he's a-making."

Lord William, then still in his woolly night-cap

(For appearances noblemen don't care a rap),

His second-best dressing-gown hastily sought,

And got up without any noise making.

"I'm exceedingly sorry," his lordship began,

"But your visit, I fear, will be fruitless.

I possess neither money, nor jewels, my man,

So your burglaring here will be bootless.

The burglar was startled, but kept a cool head,

And bowed, as his lordship, continuing, said:

"Excuse me a moment. I'll find if I can

My warm slippers, for I too am bootless."

This pleasantry put them both quite at their ease;

They discoursed of De Wet, and of Tupper.

Then the household his lordship aroused, if you please,

And invited the burglar to supper.

The burglar told tales of his hardly-won wealth,

And each drank to the other one's jolly good health.

There's a charm about informal parties like these,

And it was a most excellent supper.

Then the lord told the burglar how poor he'd become,

And of all which occasioned his lordship distress;

And the burglar—who wasn't hard-hearted like some—

His sympathy ventured thereat to express:

"I've some thoughts in my mind, if I might be so bold

As to mention them, but—no—they mustn't be told.

They are hopes which, perhaps, I might talk of to some,

But which to a lord—no, I dare not express."

"Pooh! Nonsense!" his lordship cried, "Out with it, man!

What is it, my friend, that you wish to suggest?

Rely upon me. I will do what I can.

Come! Let us see what's to be done for the best."

"I've a daughter," the burglar remarked with a sigh.

"The apple is she, so to speak, of my eye,

And she wishes to marry a lord, if she can—

And of all that I know—why, your lordship's the best.

"I am wealthy," the burglar continued, "you see,

And her fortune will really be ample:

I have given her every advantage, and she

Is a person quite up to your sample."

Lord William, at first, was inclined to look glum,

But, on thinking it over, remarked: "I will come

In the morning, to-morrow, the lady to see

If indeed she is up to the sample."

On the morrow he called, and the lady he saw,

And he found her both charming and witty;

So he married her, though for a father-in-law

He'd a burglar, which p'r'aps was a pity.

However, she made him an excellent wife,

And the burglar he settled a fortune for life

On the pair. What an excellent father-in-law!

On the whole, p'r'aps, it wasn't a pity.

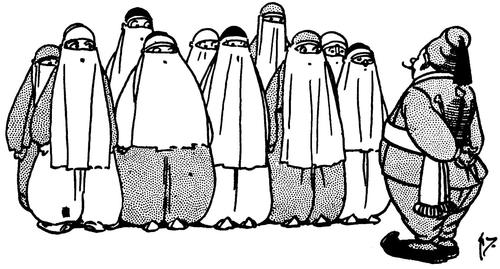

XII.

THAT OF PASHA ABDULLA BEY.

Abdulla Bey—a Pasha—had

A turn for joy and merriment:

You never caught him looking sad,

Nor glowering in discontent.

His normal attitude was one

Of calm, serene placidity;

His nature gay, and full of fun,

And free from all acidity.

A trifling instance I'll relate

Of Pasha Bey's urbanity,

The which will clearly indicate

His marvellous humanity.

He had a dozen wives or so

(In him no immorality;

For Eastern custom, as you know,

Permits, of wives, plurality).

Yes; quite a dozen wives—or more—

Abdulla had, and for a while

No sound was heard of strife or war

Within Abdulla's domicile.

But, oh! how rare it is to find

A dozen ladies who'll consent

To think as with a single mind,

And live together in content.

Abdulla's wives—altho', no doubt,

If taken individually,

Would never think of falling out,—

Collectively, could not agree.

At first, in quite a playful way,

They quarrelled—rather prettily;

Then cutting things contrived to say

About each other wittily;

Then petty jealousies and sneers

Began,—just feeble flickerings—

Which grew, alas! to bitter tears,

And fierce domestic bickerings.

You never had a dozen wives—

Of course not—so you cannot know

The grave discomfort in their lives

These Pashas sometimes undergo.

Abdulla Bey, however, he

Was not the one to be dismayed,

And doubtless you'll astounded be

To hear what wisdom he displayed.

He did not—as some would have done—

Seek angry ladies to coerce;

He did not use to any one

Expressions impolite—or worse.

No, what he did was simply this:

He stood those ladies in a row,

And said, "My dears, don't take amiss

What I'm about to say, you know.

"I find you cannot, like the birds,

Within your little nest agree,

So I'll unfold, in briefest words,

A plan which has occurred to me.

"These quarrellings, these manners lax,

In comfort means a loss for us,

So I must tie you up in sacks

And throw you in the Bosphorus."

He tied them up; he threw them in;

Then Pasha Bey, I beg to state,

Did not seek sympathy to win

By posing as disconsolate.

He mourned a week; and then, they say

(A Pasha is, of course, a catch),

Our friend, the good Abdulla Bey,

Got married to another batch.

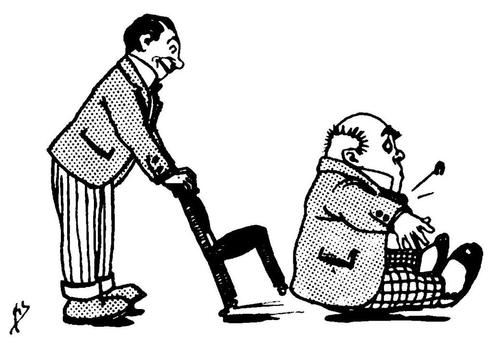

XIII.

THAT OF ALGERNON CROKER.

Permit me, and I will quite briefly relate

The sad story of Algernon Croker.

Take warning, good friends, and beware of the fate

Of this asinine practical joker,

Who early in life caused the keenest distress

To his uncle, Sir Barnaby Tatton,

By affixing a pin in the form of an S

To the chair which Sir Barnaby sat on.

His uncle had often been heard to declare

That to make him his heir he was willing;

But the point of this joke made Sir Barnaby swear

That he'd cut the boy off with a shilling.

Their anger his parents took means to express,

Tho' I may not, of course, be exact on

The particular spot—though you'll probably guess—

That young Croker was properly whacked on.

His pranks, when they presently sent him to school,

Resulted in endless disasters,

And final expulsion for playing the fool

(He made "apple-pie" beds for the masters).

Nor was he more fortunate later in life,

When courting a lady at Woking;

For he failed to secure this sweet girl for his wife

On account of his practical joking.

To her father—a person of eighteen-stone-two,

In a round-about coat and a topper—

He offered a seat; then the chair he withdrew,

And, of course, the old chap came a cropper.

Such conduct, the father exceedingly hurt,

And he wouldn't consent to the marriage;

So the daughter she married a person named Birt,

And she rides to this day in her carriage.

But these are mere trifles compared with the fate

Which o'ertook him, and which I'm recalling,

When he ventured to joke with an old Potentate,

With results which were simply appalling.

'Twas in some foreign country, far over the sea,

Where he held a small post ministerial

(An Ambassador, Consul, or something was he.

What exactly is quite immaterial).

He told the old Potentate, much to his joy,

That King Edward had sent him a present,

And handed a parcel up to the old boy,

With a smile which was childlike and pleasant.

The Potentate he, at the deuce of a pace,

At the string set to fumbling and maulin';

Then Croker laughed madly to see his blank face—

For the package had nothing at all in.

The Potentate smiled—'twas a sad, sickly smile;

And he laughed—but the laughter was hollow.

"Ha! a capital joke. It doth greatly beguile;

But," said he, "there is something to follow.

I, too, wish to play a small joke of my own,

At the which I'm remarkably clever."

Then,—a man standing by, at a nod from the throne,

Croker's head from his body did sever.

Phwat's thot yer afther sayin'—

Oi "don't look meself at all?"

Och, murder! sure ye've guessed it.

Whist! Oi'm not meself at all,

But another man entoirly,

An' Oi'd bether tell ye trooly

How ut iz Oi'm but purtendin'

That Oi'm Mr. Pat O'Dooley.

Tim Finnegan an' me, sor,

Waz a-fightin ov the blacks

In hathen foreign parts, sor,

An' yer pardon Oi would ax

If Oi mention thot the customs

In them parts iz free an' aisy,

An' the costooms—bein' mostly beads—

Iz airy-loike an' braizy.

But them blacks iz good at fightin'

An' they captured me an' Tim;

An' they marched us back in triumph

To their village—me an' him;

An' they didn't trate us badly,

As Oi'm not above confessin',

Tho' their manners—as Oi said before—

An' customs, waz disthressin'.

So Oi set meself to teachin'

The King's daughter to behave

As a perfect lady should do;

An' Oi taught the King to shave;

An' Oi added to the lady's

Scanty costoom by the prisent

Ov a waistcoat, which she thanked me for,

A-smilin' moighty plisent.

Now she wazn't bad to look at,

An' she fell in love with me,

Which was awkward for all parties,

As you prisently will see;

For on wan noight, when the village

Waz all quiet-loike an' slapin',

The King's daughter to the hut, phwere

Tim an' me lay, came a-crapin'.

An' she whispered in my ear, sor:

"Get up quick, an' come this way,

Oi'll assist ye in escapin',

If ye'll do just phwat Oi say."

An' she led me by the hand, sor;

It waz dark, the rain was pourin'

An' we safely passed the huts, sor,

Phwere the sintrys waz a snorin'

Then we ran, an' ran, an' ran, sor,

Through all the blessid noight,

An' waz many miles away, sor,

Before the day was loight.

Then the lady saw my features,

An' she stopped an' started cryin',

For she found that I waz Tim instead

Ov me, which waz most tryin'.

In the hurry an' the scurry

Ov the darkness, don't yez see,

She had made a big mistake,

An' rescued him instead ov me—

An' to me it waz confusin'

An' most hard ov realizin';

For to find yerself another person,

Sor, iz most surprisin'.

An' pwhen the lady left me,

An' Oi'd got down to the shore

An' found a ship to take me home,

Oi puzzled more an' more,

For, ov course, the woife an' family

Ov Finnegan's was moine, sor,

Tho' Oi didn't know the wan ov 'em

By hook, nor crook, nor soign, sor.

But Oi came to the decision

They belonged to me no doubt,

So directly Oi had landed

Oi began to look about.

Tim Finnegan had told me

That he lived up in Killarn'y,

An' Oi found meself that far, somehow,

By carnying an' blarney.

An' Oi found me woife an' family—

But, ach! upon my loife

Oi waz greatly disappointed

In my family an' woife,

For my woife was not a beauty,

An' her temper wazn't cheerin'

While the family—onkindly—

At their father took to jeerin'.

"Oi waz better off as Pat," thought Oi,

"Than Oi'll iver be as Tim.

Bedad! Oi'd better be meself

An' lave off bein' him.

Oi won't stay here in Killarn'y,

Phwere they trate poor Tim so coolly,

But purtend to be meself agin

In dear old Ballyhooley.'

So Oi came to Ballyhooley,

An' Oi've niver told before

To anyone the story

Oi've been tellin' to ye, sor,

An' it, all ov it, occurred, sor,

Just exactly as Oi state it,

Though, ov course, ye'll understand, sor,

Oi don't wish ye to repate it.

XV.

THAT OF THE RIVAL HAIRDRESSERS.

In the fashionable quarter

Of a fashionable town

Lived a fashionable barber,

And his name was Mister Brown.

Of hair, the most luxuriant,

This person had a crop,

And—a—so had his assistants,

And—the boy who swept the shop.

He had pleasant manners—very—

And his smile was very bland,

While his flow of conversation

Was exceptionally grand.

The difficulty was that he

Did not know when to stop;

Neither did his good assistants,

Nor—the boy who swept the shop.

He'd begin about the weather,

And remark the day was fine,

Or, perhaps, "it would be brighter

If the sun would only shine."

Or, he'd "noticed the barometer

Had fallen with a flop;

And—a—so had his assistants,

And—the boy who swept the shop."

Then the news from all the papers

(Most of which you'd heard before)

He would enter into fully,

And the latest cricket score;

Or, political opinions,

He'd be pleased with you to swop;

And—a—so would his assistants,

Or—the boy who swept the shop.

At the Stock Exchange quotations

Mister Brown was quite au fait,

And on betting, or "the fav'rit',"

He would talk in knowing way;

Then into matters personal

He'd occasionally drop,

And—a—so would his assistants,

Or—the boy who swept the shop.

He'd recommend Macassar oil,

Or someone's brilliantine,

As "a remedy for baldness."

'Twas "the finest he had seen."

And he'd "noticed that your hair of late

Was thinning on the top."

And—a—"so had his assistants,

And—the boy who swept the shop."

Now one day, nearly opposite,

Another barber came,

And opened an establishment

With quite another name.

And Brown looked out and wondered

If this man had come to stop.

And—a—so did his assistants,

And—the boy who swept the shop.

But they didn't fear their neighbour,

For the man seemed very meek.

He'd no flow of conversation,

And looked half afraid to speak.

So Brown tittered at his rival

(Whose name happened to be Knopp);

And—a—so did his assistants,

And—the boy who swept the shop.

But somehow unaccountably

Brown's custom seemed to flow

In some mysterious sort of way

To Knopp's. It was a blow.

And Brown looked very serious

To see his profits drop.

And—a—so did his assistants

And—the boy who swept the shop.

And I wondered, and I wondered

Why this falling off should be,

And I thought one day I'd step across

To Mister Knopp's to see.

I found him very busy

With—in fact—no time to stop,

And—a—so were his assistants.

And—the boy who swept his shop.

Mister Knopp was very silent,

His assistants still as mice;

All the customers were smiling,

And one whispered, "Ain't it nice?"

"Hey? You want to know the reason?

Why, deaf and dumb is Knopp,

And—a—so are his assistants,

And—the boy who sweeps the shop."

XVI.

THAT OF THE AUCTIONEER'S DREAM.

I'll proceed to the narration

Of a trifling episode

In the life of Mr. Platt,

An auctioneer,

Who was filled with jubilation

And remarked: "Well, I'll be blowed!"—

An expression rather im-

Polite, I fear.

But he dreamt he'd heard it stated

That, in future, auctioneers

Might include their near relations

In their sales;

And he felt so much elated

That he broke out into cheers,

As one's apt to do when other

Language fails.

And he thought: "Dear me, I'd better

Seize this opportunity

Of getting rid of ma-in-law,

And Jane—

('Twas his wife)—I'll not regret her;

And, indeed, it seems to me

Such a chance may really not

Occur again.

"And, indeed, while I'm about it,

I'll dispense with all the lot—

(O'er my family I've lately

Lost command)—

'Tis the best plan, never doubt it.

I'll dispose of those I've got,

And, perhaps, I'll get some others

Second-hand."

So his ma-in-law he offered

As the first lot in the sale,

And he knocked her down for two-

And-six, or less.

Then Mrs. Platt he proffered—

She was looking rather pale;

But she fetched a good round sum,

I must confess.

Sister Ann was slightly damaged,

But she went off pretty well

Considering her wooden leg,

And that;

But I can't think how he managed

His wife's grandmother to sell—

But he did it. It was very smart

Of Platt.

Several children, and the twins

(Lots from 9 to 22),

Fetched the auctioneer a tidy sum

Between 'em.

(One small boy had barked his shins,

And a twin had lost one shoe,

But they looked as well, Platt thought, as e'er

He'd seen 'em.)

Then some nephews, and some nieces,

Sundry uncles, and an aunt,

Went off at figures which were

Most surprising.

And some odds and ends of pieces

(I would tell you, but I can't

Their relationship) fetched prices

Past surmising.

It is quite enough to mention

That before the day was out

All his relatives had gone

Without reserve.

This fell in with Platt's intention,

And he said: "Without a doubt,

I shall now as happy be

As I deserve."

But he

wasn't very happy,

For he soon began to miss

Mrs. Platt, his wife, and all

The little "P's."

And the servants made him snappy;

Home was anything but bliss;

And Mr. Platt was very

Ill at ease.

So he calmly thought it over.

"On the whole, perhaps," said he,

I had better buy my fam-

Ily again,

For I find I'm not in clover,

Quite, without my Mrs. P.—

She was really not a bad sort,

Wasn't Jane."

But the persons who had bought 'em

Wouldn't part with 'em again.

Though Platt offered for their purchase

Untold gold.

For quite priceless now he thought 'em,

And, of course, could see quite plain

That in selling them he had himself

Been sold.

And he thought, with agitation

Of them lost for ever now,

And he said, "This thing has gone

Beyond a joke,"

While the beads of perspiration

Gathered thickly on his brow;

And then Mr. Platt, the auctioneer—

Awoke.

XVII.

THAT OF THE PLAIN COOK.

Miss Miriam Briggs was a plain, plain cook,

And her cooking was none too good

(Not at all like the recipes out of the book,

And, in fact, one might tell at the very first look

That things hadn't been made as they should).

Her master, a person named Lymmington-Blake,

At her cooking did constantly grieve,

And at last he declared that "a change he must make,"

For he "wanted a cook who could boil or could bake,"

And—this very plain cook—"she must leave."

So she left, and her master, the very same day,

For the Registry Office set out,

For he naturally thought it the very best way

Of procuring a cook with the smallest delay.

(You, too, would have done so, no doubt.)

But, "A cook? Goodness gracious!" the lady declared

(At the Registry Office, I mean),

"I've no cook on my books, sir, save one, and she's shared

By two families; and, sir, I've nearly despaired,

For so rare, sir, of late, cooks have been."

Where next he enquired 'twas precisely the same:

There wasn't a cook to be had.

Though quite high were the wages he'd willingly name,

And he advertised,—uselessly,—none ever came,—

Not a cook, good, indiff'rent, or bad.

What

was to be done? Mr. Lymmington-Blake

Began to grow thinner and thinner.

(Now and then it is pleasant, but quite a mistake,

To dine every day on a chop or a steak,

And have nothing besides for your dinner.)

So he said: "If I can't get a cook, then a mate

I'll endeavour to find in a wife"

(His late wife deceased, I p'r'aps ought to relate,

Four or five years before), "for this terrible state

Of things worries me out of my life."

So he looked in the papers, and read with delight

Of a "Lady of good education,

A charming complexion, eyes blue (rather light),"

Who "would to a gentleman willingly write."

She "preferred one without a relation."

Now Lymmington-Blake was an orphan from birth,

And had neither a sister nor brother,

While of uncles and aunts he'd a similar dearth,

And he thought, "Here's a lady of singular worth;

I should think we should suit one another."

So he wrote to the lady, and she wrote to him,

And the lady requested a photo,

But he thought, "I'm not young, and the picture might dim

Her affection; I'll plead, to the lady, a whim,

And refuse her my photo in toto."

"I'll be happy, however," he wrote, "to arrange

A meeting for Wednesday night.

Hampstead Heath, on the pathway, beside the old Grange,

At a quarter to eight. If you won't think it strange,

Wear a rose—I shall know you at sight."

Came Wednesday night, Mr. Lymmington-Blake

To the rendezvous all in a flutter

Himself—in a new suit of clothes—did betake;

And over and over, to save a mistake,

The speech he had thought of did mutter.

He wore a red rose, for he thought it would show

He had taken the matter to heart.

A lady was there. Was it she? Yes, or no?

Blake didn't know whether to stay or to go.

He was nervous. But what made him start?

'Twas the figure—at first he could not see her face—

Which somehow familiar did look.

Then she turned—and he ran. Do you think it was base?

I fancy that you'd have done so in his place.

It was Miriam Briggs, the plain cook.

XVIII.

THAT OF "8" AND "22."

'Twas on the "Royal Sovereign,"

Which sails from Old Swan Pier,

That Henry Phipps met Emily Green,

And—this is somewhat queer—

Aboard the ship was Obadiah,

Likewise a lady called Maria

The surnames of these people I

Cannot just now recall,

But 'tis quite immaterial,

It matters not at all.

The point is this—Phipps met Miss Green;

The sequel quickly will be seen.

He noticed her the first time when

To luncheon they went down

(The luncheon on the "Sovereign"

Is only half a-crown),

Where Obadiah gravely at

The table, with Maria, sat.

And Obadiah coughed because

Phipps looked at Emily—she at him.

Maria likewise noticed it,

And thereupon grew stern and grim,

Though neither one of all the four

Had met the other one before.

Now Emily Green was pretty, but

Maria—she was the reverse;

While Obadiah's looks were tra-

Gic—something like Macbeth's, but worse.—

And these two somehow seemed to be

Quite down on Phipps, and Miss E. G.

For when she smiled, and kindly passed

The salt—which Phipps had asked her for—

Maria tossed her head and sniffed,

And Obadiah muttered "Pshaw!"

While later on Miss E. G. thinks

She heard Maria call her "minx."

Twice on the upper deck when Phipps

Just ventured, in a casual way,

To pass appropriate remarks,

Or comment on the "perfect" day,

He caught Maria listening, and,

Close by, saw Obadiah stand.

At last, at Margate by the Sea,

The "Royal Sovereign" came to port.

Phipps hurried off and soon secured

A lodging very near The Fort

(He'd understood Miss Green to say

That she should lodge somewhere that way).

He really was annoyed to find

That Obadiah came there too,

While Miss Maria, opposite,

The parlour blinds was peering through.

Still he felt very happy, for

He saw Miss Green arrive next door.

That night he met her on the pier,

And Phipps, of course, he raised his hat.

Miss Emily Green blushed, smiled, and stopped—

It was not to be wondered at.

But Obadiah, passing by,

Transfixed them with his eagle eye.

And, later in the evening, when

The two were list'ning to the band,

Phipps—tho' perhaps he oughtn't to—

Was gently squeezing Emily's hand.

He dropped it suddenly, for there

Maria stood, with stony stare.

'Twas so on each succeeding day.

Whate'er they did, where'er they went,

There Obadiah followed them;

Maria, too. No accident

Could possibly account for this

Sad interference with their bliss.

At last Phipps, goaded to despair,

Cried: "Pray, sir—what, sir, do you wish?"

But Obadiah turned away,

Merely ejaculating "Pish!"

Then Phipps addressed Maria too,

And all he got from her was "Pooh!"

So Mr. Phipps and Emily Green

Determined something must be done.

And all one day they talked it o'er,

From early morn till setting sun.

Then, privately, the morrow fixed

For joining in the bathing,—mixed.

They knew that Obadiah would

Be present, and Maria too.

They were; and his machine was "8,"

Maria's Number "22."

They each stood glaring from their door,

Some little distance from the shore.

The tide came in, the bathers all—

Including Phipps and Emily Green—

Each sought his own—his very own—

Particular bathing-machine;

But Nos. "22" and "8"

Were left, unheeded, to their fate.

When, one by one, the horses drew

The other machines to the shore,

Phipps bribed the men to leave those two

Exactly where they were before.

(In "8," you know, was Obadiah,

And "22" contained Maria.)

The tide rose higher, carrying

The two machines quite out to sea.

The love affairs of Emily Green

And Phipps proceeded happily.

I'm not quite certain of the fate

Of either "22" or "8."

XIX.

THAT OF THE HOOLIGAN AND THE PHILANTROPIST.

Bill Basher was a Hooligan,

The terror of the town,

A reputation he possessed

For knocking people down;

On unprotected persons

Of a sudden he would spring,

And hit them with his buckle-belt,

Which hurt like anything.

One day ten stalwart constables

Bill Basher took in charge.

"We cannot such a man," said they,

"Permit to roam at large;

He causes all the populace

To go about in fear;

We'd better take him to the Court

Of Mr. Justice Dear."

To Mr. Justice Dear they went—

A tender Judge was he:

He was a great Philanthropist

(Spelt with a big, big "P").

His bump—phrenologists declared—

Of kindness was immense;

Altho' he somewhat lacked the bump

Of common, common sense.

"Dear, dear!" exclaimed the kindly Judge

A-looking very wise,

"Your conduct in arresting him

Quite fills me with surprise.

Poor fellow! Don't you see the lit-

Tle things which he has done

Were doubtless but dictated

By a sense of harmless fun?

"We really mustn't be too hard

Upon a man for that,

And I will not do more than just

Inflict a fine. That's flat!

See how he stands within the dock,

As mild as any lamb.

No! Sixpence fine. You are discharged.

Good morning, William."

Now strange to say, within a week,

Bill Basher had begun

To knock about a lot of other

People "just in fun."

He hit a young policeman

With a hammer on the head,

Until the poor young fellow

Was approximately dead.

"Good gracious!" murmured Justice Dear,

"This really is too bad,

To hit policemen on the head

Is not polite, my lad,

I must remand you for a week

To think what can be done,

And, in the meantime, please remain

In cell one twenty one."

Then, Justice Dear, he pondered thus:

"Bill Basher ought to wed

Some good and noble woman;

Then he'd very soon be led

To see the error of his ways,

And give those errors o'er."

This scheme he thought upon again,

And liked it more and more.

A daughter had good Justice Dear,

Whose name was Angeline

(The lady's name is not pronounced

To rhyme with "line," but "leen"),

Not beautiful, but dutiful

As ever she could be;

Whatever her papa desired

She did obediently.

With her he talked the matter o'er,

And told her that he thought,

In the interests of humanity,

To marry Bill she ought.

And, though she loved a barrister

Named Smith, her grief she hid

And, with a stifled sigh, prepared

To do as she was bid.

They got a special licence, and

Together quickly went

To visit Basher in his cell

And show their kind intent.

His answer it was to the point,

Though couched in language queer,

These were the very words he used:

"Wot? Marry 'er? No fear!"

Good Justice Dear was greatly shocked;

Indeed, it was a blow

To find that such ingratitude

The Hooligan should show.

So he gave to Smith, the barrister,

His daughter for a wife,

While on Bill he passed this sentence—

"Penal servitude for life."

XX.

THAT OF THE SOCIALIST AND THE EARL.

It was, I think, near Marble Arch,

Or somewhere in the Park,

A Socialist

Once shook his fist

And made this sage remark:

"It is a shime that working men,

The likes of you and me—

Poor, underfed,

Without a bed—

In such a state should be.

"When bloated aristocracy

Grows daily wuss an' wuss.

Why don't the rich

Behave as sich

An' give a bit to us?

"They've carriages and flunkeys,

Estates, an' lots of land.

Why this should be,

My friends," said he,

"I fail to understand.

"Why should they 'ave the bloomin' lot,

When, as I've said before,

It's understood

This man's as good

As that one is—or MORE?

"So what I sez, my friends, sez I,

Is: Down with all the lot,

Unless they share—

It's only fair—

With us what they have got!"

An Earl, who stood amongst the crowd,

Was very much impressed.

"Dear me," he said,

And smote his head,

"I really am distressed.

"To think that all these many years

I've lived so much at ease,

With leisure, rank,

Cash at the bank,

And luxuries like these,

"While, as this honest person says,

Our class is all to blame

That these have naught:

We really ought

To bow our heads in shame.

"My wealth unto this man I'll give,

My title I will drop,

And then I'll go

And live at Bow

And keep a chandler's shop."

The Socialist he took the wealth

The Earl put in his hands,

And bought erewhile

A house in style

And most extensive lands.

Was knighted (for some charity

Judiciously bestowed);

Within a year

Was made a Peer;

To fame was on the road.

But do not think that Fortune's smiles

From friends drew him apart,

Or hint that rude

Ingratitude

Could dwell within his heart.

You fear, perhaps, that he forgot

The worthy Earl. Ah, no!

Household supplies

He often buys

From his shop down at Bow.

XXI.

THAT OF THE RETIRED PORK-BUTCHER

AND THE SPOOK.

I may as well

Proceed to tell

About a Mister Higgs,

Who grew quite rich

In trade—the which

Was selling pork and pigs.

From trade retired,

He much desired

To rank with gentlefolk,

So bought a place

He called "The Chase,"

And furnished it—old oak.

Ancestors got

(Twelve pounds the lot,

In Tottenham Court Road);

A pedigree—

For nine pounds three,—

The Heralds' Court bestowed.

And on the wall,

Hung armour bright and strong.

"To Ethelbred"—

The label read—

De Higgs, this did belong."

'Twas quite complete,

This country seat,

Yet neighbours stayed away.

Nobody called,—

Higgs was blackballed,—

Which caused him great dismay.

"Why can it be?"

One night said he

When thinking of it o'er.

There came a knock

('Twas twelve o'clock)

Upon his chamber door.

Higgs cried, "Come in!"

A vapour thin

The keyhole wandered through.

Higgs rubbed his eyes

In mild surprise:

A ghost appeared in view.

"I beg," said he,

"You'll pardon me,

In calling rather late.

A family ghost,

I seek a post,

With wage commensurate.

My 'fiendish yell'

Is certain sure to please.

'Sepulchral tones,'

And 'rattling bones,'

I'm very good at these.

"Five bob I charge

To roam at large,

With 'clanking chains' ad lib.;

I do such things

As 'gibberings'

At one-and-three per gib.

"Or, by the week,

I merely seek

Two pounds—which is not dear;

Because I need,

Of course, no feed,

No washing, and no beer."

A bit, before

He hired the family ghost,

But, finally,

He did agree

To give to him the post.

It got about—

You know, no doubt,

How quickly such news flies—

Throughout the place,

From "Higgses Chase"

Proceeded ghostly cries.

The rumour spread,

Folks shook their head,

But dropped in one by one.

A bishop came

(Forget his name),

And then the thing was done.

For afterwards

All left their cards,

"Because," said they, "you see,

One who can boast

A family ghost

Respectable must be."

When it was due,

The "ghostes's" screw

Higgs raised—as was but right—

They often play,

In friendly way,

A game of cards at night.

XXII.

THAT OF THE POET AND THE BUCCANEERS.

It does not fall to every man

To be a minor poet,

But Inksby-Slingem he was one,

And wished the world to know it.

In almost every magazine

His dainty verses might be seen.

He'd take a piece of paper—blank,

With nothing writ upon it—

And soon a triolet 'twould be

A ballade, or a sonnet.

Pantoums,—in fact, whate'er you please,

This poet wrote, with greatest ease.

By dozens he'd turn poems out,

To Editors he'd bring 'em,

Till, quite a household word became

The name of Inksby-Slingem.

A mild exterior had he,

With dove-like personality.

His hair was dark and lank and long,

His necktie large and floppy

(Vide his portrait in the sketch

"A-smelling of a Poppy"),

And unto this young man befell

The strange adventure I'll now tell.

Aboard the good ship "Goschen,"

Which foundered, causing all but he

To perish, in the ocean,

And many days within a boat

Did Inksby-Slingem sadly float—

Yes, many days, until with joy

He saw a ship appearing;

A skull and crossbones flag it bore,

And towards him it was steering.

"This rakish-looking craft," thought he,

"I fear a pirate ship must be."

It was. Manned by a buccaneer.

And, from the very first, he

Could see the crew were wicked men,

All scowling and bloodthirsty;

Indeed, he trembled for his neck

When hoisted to their upper deck.

Indelicate the way, at least,

That he was treated—very.

They turned his pockets inside-out;

They stole his Waterbury;

His scarf-pin, and his golden rings,

His coat and—er—his other things.

Then, they ransacked his carpet-bag,

To add to his distresses,

And tumbled all his papers out,

His poems, and MSS.'s.

He threw himself upon his knees,

And cried: "I pray you, spare me these!"

"These? What are these?" the Pirate cried.

"I've not the slightest notion."

He read a verse or two—and then

Seemed filled with strange emotion.

He read some more; he heaved a sigh;

A briny tear fell from his eye.

"Dear, dear!" he sniffed, "how touching is

This poem 'To a Brother!'

It makes me think of childhood's days,

My old home, and my mother."

He read another poem through,

And passed it to his wondering crew.

They read it, and all—all but two—

Their eyes were soon a-piping;

It was a most affecting sight

To see those pirates wiping

Their eyes and noses in their griefs

On many-coloured handkerchiefs,

To make a lengthy story short,

The gentle poet's verses

Quite won those men from wicked ways,

From piratings, and curses;

And all of them, so I've heard tell,

Became quite, quite respectable.

All—all but two, and one of

themThan e'er before much worse is

For he is now a publisher,

And "pirates" Slingem's verses;

The other drives a "pirate" 'bus,

Continuing—alas!—to "cuss."

XXIII.

THAT OF THE UNDERGROUND "SULPHUR CURE."

Sulphuric smoke doth nearly choke

That person—more's the pity—

Who does the round, by Underground,

On pleasure, or on business bound,

From West End to the City.

At Gower Street I chanced to meet,

One day, a strange old party,

Who tore his hair in wild despair,

Until I thought—"I would not swear,

That you're not mad, my hearty."

"Yes, mad, quite mad. Dear me! How sad!"

I cried; for, to the porter,

He did complain—"Look here! Again

No smoke from any single train

That's passed within the quarter.

"This air's too pure! I cannot cure

My patients, if you don't, sir,

Sulphuric gas allow to pass,

Until it thickly coats the glass.

Put up with this I won't, sir!"

I noticed then some gentlemen

And ladies join the chatter—

And dear, dear, dear, they did look queer!

Thought I—"They're very ill, I fear;

I wonder what's the matter."

Surmise was vain. In came my train.

I got in. "First"—a "Smoking."

That motley crew—they got in too.

I wondered what on earth to do,

For each began a-choking.

"Pray, won't you smoke?" the old man spoke.

Thought I—"He's growing madder."

"I wish you would. 'Twould do them good.

My card I'd hand you if I could,

But have none. My name's Chadder.

"My patients these. Now, if you please!"

He cried, in tones commanding,

And gave three raps, "I think, perhaps,

We'd best begin. Undo your wraps!"

This passed my understanding.

"Put out your tongues! Inflate your lungs!"

His patients all got ready;

Their wraps thrown off, they each did doff

Their respirator—spite their cough—

And took breaths long and steady.

"Inhale! Inhale! And do not fail

The air you take to swallow!"

They gasped, and wheezed, and coughed, and sneezed.

Their "doctor," he looked mighty pleased.

Expecting me to follow.

"Pray, tell me why, good sir!" gasped I,

"Before I lose my senses,

Why ever you such strange things do?

To know this, I confess my cu-

Riosity immense is."

In accents mild he spoke, and smiled.

"Delighted! I assure you.

We take the air—nay! do not stare;

Should aught your normal health impair,

This 'sulphur cure' will cure you.

"I undertake, quite well to make

Patients,—whate'er they're ailing.

Each day we meet, proceed en suite

From Edgware Road to Gower Street,

And back again—inhaling.

"That sulphur's good, 'tis understood,

But, I would briefly mention,

The simple way—as one may say,—

In which we take it, day by day,

Is quite my own invention.

"Profits? Ah, yes, I must confess

I make a tidy bit, sir?

Tho' Mr. Perkes', and Mr. Yerkes

'S system—if it only works—

Will put a stop to it, sir."

A stifled sigh, a tear-dimmed eye

Betrayed his agitation.

"Down here there'll be no smoke," said he,

"When run by electricity.

Excuse me! Here's our station!"

He fussed about, and got them out,

(Those invalids I mean, sir,)

Then raised his hat; I bowed at that,

And then, remaining where I sat,

Went on to Turnham Green, sir.

XXIV.

THAT OF THE FAIRY GRANDMOTHER AND THE

COMPANY PROMOTER.

A Company Promoter was Septimus Sharpe,

And the subject is he of this ditty;

He'd his name—nothing more—

Painted on the glass door

Of an office high up on the toppermost floor

Of a house in Throgmorton Street, City.

The Companies which he had promoted, so far,