CANTO XI

"O thou Almighty Father, who dost make

The heavens thy dwelling, not in bounds confin'd,

But that with love intenser there thou view'st

Thy primal effluence, hallow'd be thy name:

Join each created being to extol

Thy might, for worthy humblest thanks and praise

Is thy blest Spirit. May thy kingdom's peace

Come unto us; for we, unless it come,

With all our striving thither tend in vain.

As of their will the angels unto thee

Tender meet sacrifice, circling thy throne

With loud hosannas, so of theirs be done

By saintly men on earth. Grant us this day

Our daily manna, without which he roams

Through this rough desert retrograde, who most

Toils to advance his steps. As we to each

Pardon the evil done us, pardon thou

Benign, and of our merit take no count.

'Gainst the old adversary prove thou not

Our virtue easily subdu'd; but free

From his incitements and defeat his wiles.

This last petition, dearest Lord! is made

Not for ourselves, since that were needless now,

But for their sakes who after us remain."

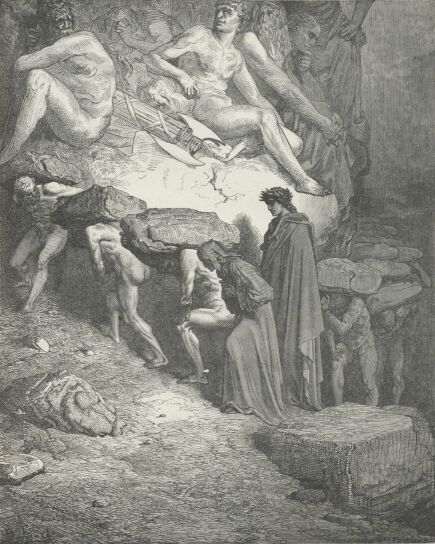

Thus for themselves and us good speed imploring,

Those spirits went beneath a weight like that

We sometimes feel in dreams, all, sore beset,

But with unequal anguish, wearied all,

Round the first circuit, purging as they go,

The world's gross darkness off: In our behalf

If there vows still be offer'd, what can here

For them be vow'd and done by such, whose wills

Have root of goodness in them? Well beseems

That we should help them wash away the stains

They carried hence, that so made pure and light,

They may spring upward to the starry spheres.

"Ah! so may mercy-temper'd justice rid

Your burdens speedily, that ye have power

To stretch your wing, which e'en to your desire

Shall lift you, as ye show us on which hand

Toward the ladder leads the shortest way.

And if there be more passages than one,

Instruct us of that easiest to ascend;

For this man who comes with me, and bears yet

The charge of fleshly raiment Adam left him,

Despite his better will but slowly mounts."

From whom the answer came unto these words,

Which my guide spake, appear'd not; but 'twas said.

"Along the bank to rightward come with us,

And ye shall find a pass that mocks not toil

Of living man to climb: and were it not

That I am hinder'd by the rock, wherewith

This arrogant neck is tam'd, whence needs I stoop

My visage to the ground, him, who yet lives,

Whose name thou speak'st not him I fain would view.

To mark if e'er I knew him? and to crave

His pity for the fardel that I bear.

I was of Latiun, of a Tuscan horn

A mighty one: Aldobranlesco's name

My sire's, I know not if ye e'er have heard.

My old blood and forefathers' gallant deeds

Made me so haughty, that I clean forgot

The common mother, and to such excess,

Wax'd in my scorn of all men, that I fell,

Fell therefore; by what fate Sienna's sons,

Each child in Campagnatico, can tell.

I am Omberto; not me only pride

Hath injur'd, but my kindred all involv'd

In mischief with her. Here my lot ordains

Under this weight to groan, till I appease

God's angry justice, since I did it not

Amongst the living, here amongst the dead."

List'ning I bent my visage down: and one

(Not he who spake) twisted beneath the weight

That urg'd him, saw me, knew me straight, and call'd,

Holding his eyes With difficulty fix'd

Intent upon me, stooping as I went

Companion of their way. "O!" I exclaim'd,

"Art thou not Oderigi, art not thou

Agobbio's glory, glory of that art

Which they of Paris call the limmer's skill?"

"Brother!" said he, "with tints that gayer smile,

Bolognian Franco's pencil lines the leaves.

His all the honour now; mine borrow'd light.

In truth I had not been thus courteous to him,

The whilst I liv'd, through eagerness of zeal

For that pre-eminence my heart was bent on.

Here of such pride the forfeiture is paid.

Nor were I even here; if, able still

To sin, I had not turn'd me unto God.

O powers of man! how vain your glory, nipp'd

E'en in its height of verdure, if an age

Less bright succeed not! Cimabue thought

To lord it over painting's field; and now

The cry is Giotto's, and his name eclips'd.

Thus hath one Guido from the other snatch'd

The letter'd prize: and he perhaps is born,

Who shall drive either from their nest. The noise

Of worldly fame is but a blast of wind,

That blows from divers points, and shifts its name

Shifting the point it blows from. Shalt thou more

Live in the mouths of mankind, if thy flesh

Part shrivel'd from thee, than if thou hadst died,

Before the coral and the pap were left,

Or ere some thousand years have passed? and that

Is, to eternity compar'd, a space,

Briefer than is the twinkling of an eye

To the heaven's slowest orb. He there who treads

So leisurely before me, far and wide

Through Tuscany resounded once; and now

Is in Sienna scarce with whispers nam'd:

There was he sov'reign, when destruction caught

The madd'ning rage of Florence, in that day

Proud as she now is loathsome. Your renown

Is as the herb, whose hue doth come and go,

And his might withers it, by whom it sprang

Crude from the lap of earth." I thus to him:

"True are thy sayings: to my heart they breathe

The kindly spirit of meekness, and allay

What tumours rankle there. But who is he

Of whom thou spak'st but now?"--"This," he replied,

"Is Provenzano. He is here, because

He reach'd, with grasp presumptuous, at the sway

Of all Sienna. Thus he still hath gone,

Thus goeth never-resting, since he died.

Such is th' acquittance render'd back of him,

Who, beyond measure, dar'd on earth." I then:

"If soul that to the verge of life delays

Repentance, linger in that lower space,

Nor hither mount, unless good prayers befriend,

How chanc'd admittance was vouchsaf'd to him?"

"When at his glory's topmost height," said he,

"Respect of dignity all cast aside,

Freely He fix'd him on Sienna's plain,

A suitor to redeem his suff'ring friend,

Who languish'd in the prison-house of Charles,

Nor for his sake refus'd through every vein

To tremble. More I will not say; and dark,

I know, my words are, but thy neighbours soon

Shall help thee to a comment on the text.

This is the work, that from these limits freed him."

CANTO XII

With equal pace as oxen in the yoke,

I with that laden spirit journey'd on

Long as the mild instructor suffer'd me;

But when he bade me quit him, and proceed

(For "here," said he, "behooves with sail and oars

Each man, as best he may, push on his bark"),

Upright, as one dispos'd for speed, I rais'd

My body, still in thought submissive bow'd.

I now my leader's track not loth pursued;

And each had shown how light we far'd along

When thus he warn'd me: "Bend thine eyesight down:

For thou to ease the way shall find it good

To ruminate the bed beneath thy feet."

As in memorial of the buried, drawn

Upon earth-level tombs, the sculptur'd form

Of what was once, appears (at sight whereof

Tears often stream forth by remembrance wak'd,

Whose sacred stings the piteous only feel),

So saw I there, but with more curious skill

Of portraiture o'erwrought, whate'er of space

From forth the mountain stretches. On one part

Him I beheld, above all creatures erst

Created noblest, light'ning fall from heaven:

On th' other side with bolt celestial pierc'd

Briareus: cumb'ring earth he lay through dint

Of mortal ice-stroke. The Thymbraean god

With Mars, I saw, and Pallas, round their sire,

Arm'd still, and gazing on the giant's limbs

Strewn o'er th' ethereal field. Nimrod I saw:

At foot of the stupendous work he stood,

As if bewilder'd, looking on the crowd

Leagued in his proud attempt on Sennaar's plain.

O Niobe! in what a trance of woe

Thee I beheld, upon that highway drawn,

Sev'n sons on either side thee slain! O Saul!

How ghastly didst thou look! on thine own sword

Expiring in Gilboa, from that hour

Ne'er visited with rain from heav'n or dew!

O fond Arachne! thee I also saw

Half spider now in anguish crawling up

Th' unfinish'd web thou weaved'st to thy bane!

O Rehoboam! here thy shape doth seem

Louring no more defiance! but fear-smote

With none to chase him in his chariot whirl'd.

Was shown beside upon the solid floor

How dear Alcmaeon forc'd his mother rate

That ornament in evil hour receiv'd:

How in the temple on Sennacherib fell

His sons, and how a corpse they left him there.

Was shown the scath and cruel mangling made

By Tomyris on Cyrus, when she cried:

"Blood thou didst thirst for, take thy fill of blood!"

Was shown how routed in the battle fled

Th' Assyrians, Holofernes slain, and e'en

The relics of the carnage. Troy I mark'd

In ashes and in caverns. Oh! how fall'n,

How abject, Ilion, was thy semblance there!

What master of the pencil or the style

Had trac'd the shades and lines, that might have made

The subtlest workman wonder? Dead the dead,

The living seem'd alive; with clearer view

His eye beheld not who beheld the truth,

Than mine what I did tread on, while I went

Low bending. Now swell out; and with stiff necks

Pass on, ye sons of Eve! veil not your looks,

Lest they descry the evil of your path!

I noted not (so busied was my thought)

How much we now had circled of the mount,

And of his course yet more the sun had spent,

When he, who with still wakeful caution went,

Admonish'd: "Raise thou up thy head: for know

Time is not now for slow suspense. Behold

That way an angel hasting towards us! Lo

Where duly the sixth handmaid doth return

From service on the day. Wear thou in look

And gesture seemly grace of reverent awe,

That gladly he may forward us aloft.

Consider that this day ne'er dawns again."

Time's loss he had so often warn'd me 'gainst,

I could not miss the scope at which he aim'd.

The goodly shape approach'd us, snowy white

In vesture, and with visage casting streams

Of tremulous lustre like the matin star.

His arms he open'd, then his wings; and spake:

"Onward: the steps, behold! are near; and now

Th' ascent is without difficulty gain'd."

A scanty few are they, who when they hear

Such tidings, hasten. O ye race of men

Though born to soar, why suffer ye a wind

So slight to baffle ye? He led us on

Where the rock parted; here against my front

Did beat his wings, then promis'd I should fare

In safety on my way. As to ascend

That steep, upon whose brow the chapel stands

(O'er Rubaconte, looking lordly down

On the well-guided city,) up the right

Th' impetuous rise is broken by the steps

Carv'd in that old and simple age, when still

The registry and label rested safe;

Thus is th' acclivity reliev'd, which here

Precipitous from the other circuit falls:

But on each hand the tall cliff presses close.

As ent'ring there we turn'd, voices, in strain

Ineffable, sang: "Blessed are the poor

In spirit." Ah how far unlike to these

The straits of hell; here songs to usher us,

There shrieks of woe! We climb the holy stairs:

And lighter to myself by far I seem'd

Than on the plain before, whence thus I spake:

"Say, master, of what heavy thing have I

Been lighten'd, that scarce aught the sense of toil

Affects me journeying?" He in few replied:

"When sin's broad characters, that yet remain

Upon thy temples, though well nigh effac'd,

Shall be, as one is, all clean razed out,

Then shall thy feet by heartiness of will

Be so o'ercome, they not alone shall feel

No sense of labour, but delight much more

Shall wait them urg'd along their upward way."

Then like to one, upon whose head is plac'd

Somewhat he deems not of but from the becks

Of others as they pass him by; his hand

Lends therefore help to' assure him, searches, finds,

And well performs such office as the eye

Wants power to execute: so stretching forth

The fingers of my right hand, did I find

Six only of the letters, which his sword

Who bare the keys had trac'd upon my brow.

The leader, as he mark'd mine action, smil'd.

CANTO XIII

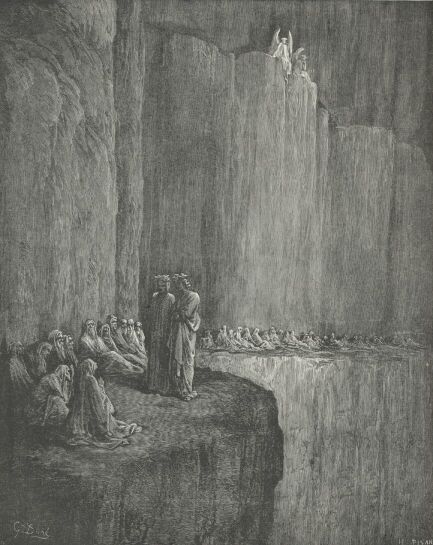

We reach'd the summit of the scale, and stood

Upon the second buttress of that mount

Which healeth him who climbs. A cornice there,

Like to the former, girdles round the hill;

Save that its arch with sweep less ample bends.

Shadow nor image there is seen; all smooth

The rampart and the path, reflecting nought

But the rock's sullen hue. "If here we wait

For some to question," said the bard, "I fear

Our choice may haply meet too long delay."

Then fixedly upon the sun his eyes

He fastn'd, made his right the central point

From whence to move, and turn'd the left aside.

"O pleasant light, my confidence and hope,

Conduct us thou," he cried, "on this new way,

Where now I venture, leading to the bourn

We seek. The universal world to thee

Owes warmth and lustre. If no other cause

Forbid, thy beams should ever be our guide."

Far, as is measur'd for a mile on earth,

In brief space had we journey'd; such prompt will

Impell'd; and towards us flying, now were heard

Spirits invisible, who courteously

Unto love's table bade the welcome guest.

The voice, that first? flew by, call'd forth aloud,

"They have no wine;" so on behind us past,

Those sounds reiterating, nor yet lost

In the faint distance, when another came

Crying, "I am Orestes," and alike

Wing'd its fleet way. "Oh father!" I exclaim'd,

"What tongues are these?" and as I question'd, lo!

A third exclaiming, "Love ye those have wrong'd you."

"This circuit," said my teacher, "knots the scourge

For envy, and the cords are therefore drawn

By charity's correcting hand. The curb

Is of a harsher sound, as thou shalt hear

(If I deem rightly), ere thou reach the pass,

Where pardon sets them free. But fix thine eyes

Intently through the air, and thou shalt see

A multitude before thee seated, each

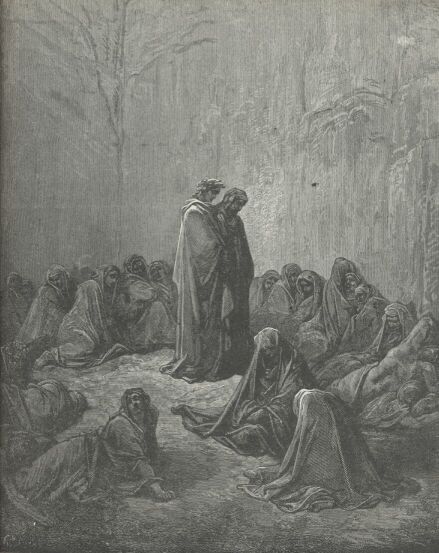

Along the shelving grot." Then more than erst

I op'd my eyes, before me view'd, and saw

Shadows with garments dark as was the rock;

And when we pass'd a little forth, I heard

A crying, "Blessed Mary! pray for us,

Michael and Peter! all ye saintly host!"

I do not think there walks on earth this day

Man so remorseless, that he hath not yearn'd

With pity at the sight that next I saw.

Mine eyes a load of sorrow teemed, when now

I stood so near them, that their semblances

Came clearly to my view. Of sackcloth vile

Their cov'ring seem'd; and on his shoulder one

Did stay another, leaning, and all lean'd

Against the cliff. E'en thus the blind and poor,

Near the confessionals, to crave an alms,

Stand, each his head upon his fellow's sunk,

So most to stir compassion, not by sound

Of words alone, but that, which moves not less,

The sight of mis'ry. And as never beam

Of noonday visiteth the eyeless man,

E'en so was heav'n a niggard unto these

Of his fair light; for, through the orbs of all,

A thread of wire, impiercing, knits them up,

As for the taming of a haggard hawk.

It were a wrong, methought, to pass and look

On others, yet myself the while unseen.

To my sage counsel therefore did I turn.

He knew the meaning of the mute appeal,

Nor waited for my questioning, but said:

"Speak; and be brief, be subtle in thy words."

On that part of the cornice, whence no rim

Engarlands its steep fall, did Virgil come;

On the' other side me were the spirits, their cheeks

Bathing devout with penitential tears,

That through the dread impalement forc'd a way.

I turn'd me to them, and "O shades!" said I,

"Assur'd that to your eyes unveil'd shall shine

The lofty light, sole object of your wish,

So may heaven's grace clear whatsoe'er of foam

Floats turbid on the conscience, that thenceforth

The stream of mind roll limpid from its source,

As ye declare (for so shall ye impart

A boon I dearly prize) if any soul

Of Latium dwell among ye; and perchance

That soul may profit, if I learn so much."

"My brother, we are each one citizens

Of one true city. Any thou wouldst say,

Who lived a stranger in Italia's land."

So heard I answering, as appeal'd, a voice

That onward came some space from whence I stood.

A spirit I noted, in whose look was mark'd

Expectance. Ask ye how? The chin was rais'd

As in one reft of sight. "Spirit," said I,

"Who for thy rise are tutoring (if thou be

That which didst answer to me,) or by place

Or name, disclose thyself, that I may know thee."

"I was," it answer'd, "of Sienna: here

I cleanse away with these the evil life,

Soliciting with tears that He, who is,

Vouchsafe him to us. Though Sapia nam'd

In sapience I excell'd not, gladder far

Of others' hurt, than of the good befell me.

That thou mayst own I now deceive thee not,

Hear, if my folly were not as I speak it.

When now my years slop'd waning down the arch,

It so bechanc'd, my fellow citizens

Near Colle met their enemies in the field,

And I pray'd God to grant what He had will'd.

There were they vanquish'd, and betook themselves

Unto the bitter passages of flight.

I mark'd the hunt, and waxing out of bounds

In gladness, lifted up my shameless brow,

And like the merlin cheated by a gleam,

Cried, "It is over. Heav'n! I fear thee not."

Upon my verge of life I wish'd for peace

With God; nor repentance had supplied

What I did lack of duty, were it not

The hermit Piero, touch'd with charity,

In his devout orisons thought on me.

"But who art thou that question'st of our state,

Who go'st to my belief, with lids unclos'd,

And breathest in thy talk?"--"Mine eyes," said I,

"May yet be here ta'en from me; but not long;

For they have not offended grievously

With envious glances. But the woe beneath

Urges my soul with more exceeding dread.

That nether load already weighs me down."

She thus: "Who then amongst us here aloft

Hath brought thee, if thou weenest to return?"

"He," answer'd I, "who standeth mute beside me.

I live: of me ask therefore, chosen spirit,

If thou desire I yonder yet should move

For thee my mortal feet."--"Oh!" she replied,

"This is so strange a thing, it is great sign

That God doth love thee. Therefore with thy prayer

Sometime assist me: and by that I crave,

Which most thou covetest, that if thy feet

E'er tread on Tuscan soil, thou save my fame

Amongst my kindred. Them shalt thou behold

With that vain multitude, who set their hope

On Telamone's haven, there to fail

Confounded, more shall when the fancied stream

They sought of Dian call'd: but they who lead

Their navies, more than ruin'd hopes shall mourn."

CANTO XIV

"Say who is he around our mountain winds,

Or ever death has prun'd his wing for flight,

That opes his eyes and covers them at will?"

"I know not who he is, but know thus much

He comes not singly. Do thou ask of him,

For thou art nearer to him, and take heed

Accost him gently, so that he may speak."

Thus on the right two Spirits bending each

Toward the other, talk'd of me, then both

Addressing me, their faces backward lean'd,

And thus the one began: "O soul, who yet

Pent in the body, tendest towards the sky!

For charity, we pray thee' comfort us,

Recounting whence thou com'st, and who thou art:

For thou dost make us at the favour shown thee

Marvel, as at a thing that ne'er hath been."

"There stretches through the midst of Tuscany,"

I straight began: "a brooklet, whose well-head

Springs up in Falterona, with his race

Not satisfied, when he some hundred miles

Hath measur'd. From his banks bring, I this frame.

To tell you who I am were words misspent:

For yet my name scarce sounds on rumour's lip."

"If well I do incorp'rate with my thought

The meaning of thy speech," said he, who first

Addrest me, "thou dost speak of Arno's wave."

To whom the other: "Why hath he conceal'd

The title of that river, as a man

Doth of some horrible thing?" The spirit, who

Thereof was question'd, did acquit him thus:

"I know not: but 'tis fitting well the name

Should perish of that vale; for from the source

Where teems so plenteously the Alpine steep

Maim'd of Pelorus, (that doth scarcely pass

Beyond that limit,) even to the point

Whereunto ocean is restor'd, what heaven

Drains from th' exhaustless store for all earth's streams,

Throughout the space is virtue worried down,

As 'twere a snake, by all, for mortal foe,

Or through disastrous influence on the place,

Or else distortion of misguided wills,

That custom goads to evil: whence in those,

The dwellers in that miserable vale,

Nature is so transform'd, it seems as they

Had shar'd of Circe's feeding. 'Midst brute swine,

Worthier of acorns than of other food

Created for man's use, he shapeth first

His obscure way; then, sloping onward, finds

Curs, snarlers more in spite than power, from whom

He turns with scorn aside: still journeying down,

By how much more the curst and luckless foss

Swells out to largeness, e'en so much it finds

Dogs turning into wolves. Descending still

Through yet more hollow eddies, next he meets

A race of foxes, so replete with craft,

They do not fear that skill can master it.

Nor will I cease because my words are heard

By other ears than thine. It shall be well

For this man, if he keep in memory

What from no erring Spirit I reveal.

Lo! I behold thy grandson, that becomes

A hunter of those wolves, upon the shore

Of the fierce stream, and cows them all with dread:

Their flesh yet living sets he up to sale,

Then like an aged beast to slaughter dooms.

Many of life he reaves, himself of worth

And goodly estimation. Smear'd with gore

Mark how he issues from the rueful wood,

Leaving such havoc, that in thousand years

It spreads not to prime lustihood again."

As one, who tidings hears of woe to come,

Changes his looks perturb'd, from whate'er part

The peril grasp him, so beheld I change

That spirit, who had turn'd to listen, struck

With sadness, soon as he had caught the word.

His visage and the other's speech did raise

Desire in me to know the names of both,

whereof with meek entreaty I inquir'd.

The shade, who late addrest me, thus resum'd:

"Thy wish imports that I vouchsafe to do

For thy sake what thou wilt not do for mine.

But since God's will is that so largely shine

His grace in thee, I will be liberal too.

Guido of Duca know then that I am.

Envy so parch'd my blood, that had I seen

A fellow man made joyous, thou hadst mark'd

A livid paleness overspread my cheek.

Such harvest reap I of the seed I sow'd.

O man, why place thy heart where there doth need

Exclusion of participants in good?

This is Rinieri's spirit, this the boast

And honour of the house of Calboli,

Where of his worth no heritage remains.

Nor his the only blood, that hath been stript

('twixt Po, the mount, the Reno, and the shore,)

Of all that truth or fancy asks for bliss;

But in those limits such a growth has sprung

Of rank and venom'd roots, as long would mock

Slow culture's toil. Where is good Lizio? where

Manardi, Traversalo, and Carpigna?

O bastard slips of old Romagna's line!

When in Bologna the low artisan,

And in Faenza yon Bernardin sprouts,

A gentle cyon from ignoble stem.

Wonder not, Tuscan, if thou see me weep,

When I recall to mind those once lov'd names,

Guido of Prata, and of Azzo him

That dwelt with you; Tignoso and his troop,

With Traversaro's house and Anastagio's,

(Each race disherited) and beside these,

The ladies and the knights, the toils and ease,

That witch'd us into love and courtesy;

Where now such malice reigns in recreant hearts.

O Brettinoro! wherefore tarriest still,

Since forth of thee thy family hath gone,

And many, hating evil, join'd their steps?

Well doeth he, that bids his lineage cease,

Bagnacavallo; Castracaro ill,

And Conio worse, who care to propagate

A race of Counties from such blood as theirs.

Well shall ye also do, Pagani, then

When from amongst you tries your demon child.

Not so, howe'er, that henceforth there remain

True proof of what ye were. O Hugolin!

Thou sprung of Fantolini's line! thy name

Is safe, since none is look'd for after thee

To cloud its lustre, warping from thy stock.

But, Tuscan, go thy ways; for now I take

Far more delight in weeping than in words.

Such pity for your sakes hath wrung my heart."

We knew those gentle spirits at parting heard

Our steps. Their silence therefore of our way

Assur'd us. Soon as we had quitted them,

Advancing onward, lo! a voice that seem'd

Like vollied light'ning, when it rives the air,

Met us, and shouted, "Whosoever finds

Will slay me," then fled from us, as the bolt

Lanc'd sudden from a downward-rushing cloud.

When it had giv'n short truce unto our hearing,

Behold the other with a crash as loud

As the quick-following thunder: "Mark in me

Aglauros turn'd to rock." I at the sound

Retreating drew more closely to my guide.

Now in mute stillness rested all the air:

And thus he spake: "There was the galling bit.

But your old enemy so baits his hook,

He drags you eager to him. Hence nor curb

Avails you, nor reclaiming call. Heav'n calls

And round about you wheeling courts your gaze

With everlasting beauties. Yet your eye

Turns with fond doting still upon the earth.

Therefore He smites you who discerneth all."

CANTO XV

As much as 'twixt the third hour's close and dawn,

Appeareth of heav'n's sphere, that ever whirls

As restless as an infant in his play,

So much appear'd remaining to the sun

Of his slope journey towards the western goal.

Evening was there, and here the noon of night;

and full upon our forehead smote the beams.

For round the mountain, circling, so our path

Had led us, that toward the sun-set now

Direct we journey'd: when I felt a weight

Of more exceeding splendour, than before,

Press on my front. The cause unknown, amaze

Possess'd me, and both hands against my brow

Lifting, I interpos'd them, as a screen,

That of its gorgeous superflux of light

Clipp'd the diminish'd orb. As when the ray,

Striking On water or the surface clear

Of mirror, leaps unto the opposite part,

Ascending at a glance, e'en as it fell,

(And so much differs from the stone, that falls)

Through equal space, as practice skill hath shown;

Thus with refracted light before me seemed

The ground there smitten; whence in sudden haste

My sight recoil'd. "What is this, sire belov'd!

'Gainst which I strive to shield the sight in vain?"

Cried I, "and which towards us moving seems?"

"Marvel not, if the family of heav'n,"

He answer'd, "yet with dazzling radiance dim

Thy sense it is a messenger who comes,

Inviting man's ascent. Such sights ere long,

Not grievous, shall impart to thee delight,

As thy perception is by nature wrought

Up to their pitch." The blessed angel, soon

As we had reach'd him, hail'd us with glad voice:

"Here enter on a ladder far less steep

Than ye have yet encounter'd." We forthwith

Ascending, heard behind us chanted sweet,

"Blessed the merciful," and "happy thou!

That conquer'st." Lonely each, my guide and I

Pursued our upward way; and as we went,

Some profit from his words I hop'd to win,

And thus of him inquiring, fram'd my speech:

"What meant Romagna's spirit, when he spake

Of bliss exclusive with no partner shar'd?"

He straight replied: "No wonder, since he knows,

What sorrow waits on his own worst defect,

If he chide others, that they less may mourn.

Because ye point your wishes at a mark,

Where, by communion of possessors, part

Is lessen'd, envy bloweth up the sighs of men.

No fear of that might touch ye, if the love

Of higher sphere exalted your desire.

For there, by how much more they call it ours,

So much propriety of each in good

Increases more, and heighten'd charity

Wraps that fair cloister in a brighter flame."

"Now lack I satisfaction more," said I,

"Than if thou hadst been silent at the first,

And doubt more gathers on my lab'ring thought.

How can it chance, that good distributed,

The many, that possess it, makes more rich,

Than if 't were shar'd by few?" He answering thus:

"Thy mind, reverting still to things of earth,

Strikes darkness from true light. The highest good

Unlimited, ineffable, doth so speed

To love, as beam to lucid body darts,

Giving as much of ardour as it finds.

The sempiternal effluence streams abroad

Spreading, wherever charity extends.

So that the more aspirants to that bliss

Are multiplied, more good is there to love,

And more is lov'd; as mirrors, that reflect,

Each unto other, propagated light.

If these my words avail not to allay

Thy thirsting, Beatrice thou shalt see,

Who of this want, and of all else thou hast,

Shall rid thee to the full. Provide but thou

That from thy temples may be soon eras'd,

E'en as the two already, those five scars,

That when they pain thee worst, then kindliest heal,"

"Thou," I had said, "content'st me," when I saw

The other round was gain'd, and wond'ring eyes

Did keep me mute. There suddenly I seem'd

By an ecstatic vision wrapt away;

And in a temple saw, methought, a crowd

Of many persons; and at th' entrance stood

A dame, whose sweet demeanour did express

A mother's love, who said, "Child! why hast thou

Dealt with us thus? Behold thy sire and I

Sorrowing have sought thee;" and so held her peace,

And straight the vision fled. A female next

Appear'd before me, down whose visage cours'd

Those waters, that grief forces out from one

By deep resentment stung, who seem'd to say:

"If thou, Pisistratus, be lord indeed

Over this city, nam'd with such debate

Of adverse gods, and whence each science sparkles,

Avenge thee of those arms, whose bold embrace

Hath clasp'd our daughter; "and to fuel, meseem'd,

Benign and meek, with visage undisturb'd,

Her sovran spake: "How shall we those requite,

Who wish us evil, if we thus condemn

The man that loves us?" After that I saw

A multitude, in fury burning, slay

With stones a stripling youth, and shout amain

"Destroy, destroy!" and him I saw, who bow'd

Heavy with death unto the ground, yet made

His eyes, unfolded upward, gates to heav'n,

Praying forgiveness of th' Almighty Sire,

Amidst that cruel conflict, on his foes,

With looks, that With compassion to their aim.

Soon as my spirit, from her airy flight

Returning, sought again the things, whose truth

Depends not on her shaping, I observ'd

How she had rov'd to no unreal scenes

Meanwhile the leader, who might see I mov'd,

As one, who struggles to shake off his sleep,

Exclaim'd: "What ails thee, that thou canst not hold

Thy footing firm, but more than half a league

Hast travel'd with clos'd eyes and tott'ring gait,

Like to a man by wine or sleep o'ercharg'd?"

"Beloved father! so thou deign," said I,

"To listen, I will tell thee what appear'd

Before me, when so fail'd my sinking steps."

He thus: "Not if thy Countenance were mask'd

With hundred vizards, could a thought of thine

How small soe'er, elude me. What thou saw'st

Was shown, that freely thou mightst ope thy heart

To the waters of peace, that flow diffus'd

From their eternal fountain. I not ask'd,

What ails thee? for such cause as he doth, who

Looks only with that eye which sees no more,

When spiritless the body lies; but ask'd,

To give fresh vigour to thy foot. Such goads

The slow and loit'ring need; that they be found

Not wanting, when their hour of watch returns."

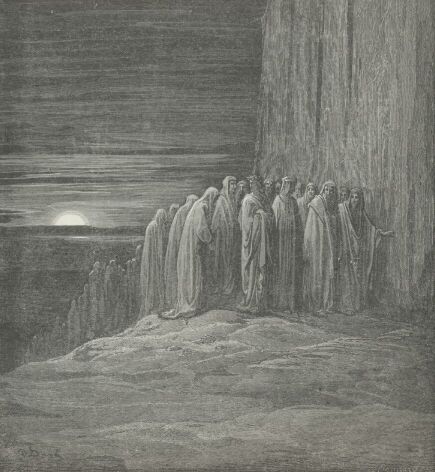

So on we journey'd through the evening sky

Gazing intent, far onward, as our eyes

With level view could stretch against the bright

Vespertine ray: and lo! by slow degrees

Gath'ring, a fog made tow'rds us, dark as night.

There was no room for 'scaping; and that mist

Bereft us, both of sight and the pure air.

CANTO XVI

Hell's dunnest gloom, or night unlustrous, dark,

Of every planes 'reft, and pall'd in clouds,

Did never spread before the sight a veil

In thickness like that fog, nor to the sense

So palpable and gross. Ent'ring its shade,

Mine eye endured not with unclosed lids;

Which marking, near me drew the faithful guide,

Offering me his shoulder for a stay.

As the blind man behind his leader walks,

Lest he should err, or stumble unawares

On what might harm him, or perhaps destroy,

I journey'd through that bitter air and foul,

Still list'ning to my escort's warning voice,

"Look that from me thou part not." Straight I heard

Voices, and each one seem'd to pray for peace,

And for compassion, to the Lamb of God

That taketh sins away. Their prelude still

Was "Agnus Dei," and through all the choir,

One voice, one measure ran, that perfect seem'd

The concord of their song. "Are these I hear

Spirits, O master?" I exclaim'd; and he:

"Thou aim'st aright: these loose the bonds of wrath."

"Now who art thou, that through our smoke dost cleave?

And speak'st of us, as thou thyself e'en yet

Dividest time by calends?" So one voice

Bespake me; whence my master said: "Reply;

And ask, if upward hence the passage lead."

"O being! who dost make thee pure, to stand

Beautiful once more in thy Maker's sight!

Along with me: and thou shalt hear and wonder."

Thus I, whereto the spirit answering spake:

"Long as 't is lawful for me, shall my steps

Follow on thine; and since the cloudy smoke

Forbids the seeing, hearing in its stead

Shall keep us join'd." I then forthwith began

"Yet in my mortal swathing, I ascend

To higher regions, and am hither come

Through the fearful agony of hell.

And, if so largely God hath doled his grace,

That, clean beside all modern precedent,

He wills me to behold his kingly state,

From me conceal not who thou wast, ere death

Had loos'd thee; but instruct me: and instruct

If rightly to the pass I tend; thy words

The way directing as a safe escort."

"I was of Lombardy, and Marco call'd:

Not inexperienc'd of the world, that worth

I still affected, from which all have turn'd

The nerveless bow aside. Thy course tends right

Unto the summit:" and, replying thus,

He added, "I beseech thee pray for me,

When thou shalt come aloft." And I to him:

"Accept my faith for pledge I will perform

What thou requirest. Yet one doubt remains,

That wrings me sorely, if I solve it not,

Singly before it urg'd me, doubled now

By thine opinion, when I couple that

With one elsewhere declar'd, each strength'ning other.

The world indeed is even so forlorn

Of all good as thou speak'st it and so swarms

With every evil. Yet, beseech thee, point

The cause out to me, that myself may see,

And unto others show it: for in heaven

One places it, and one on earth below."

Then heaving forth a deep and audible sigh,

"Brother!" he thus began, "the world is blind;

And thou in truth com'st from it. Ye, who live,

Do so each cause refer to heav'n above,

E'en as its motion of necessity

Drew with it all that moves. If this were so,

Free choice in you were none; nor justice would

There should be joy for virtue, woe for ill.

Your movements have their primal bent from heaven;

Not all; yet said I all; what then ensues?

Light have ye still to follow evil or good,

And of the will free power, which, if it stand

Firm and unwearied in Heav'n's first assay,

Conquers at last, so it be cherish'd well,

Triumphant over all. To mightier force,

To better nature subject, ye abide

Free, not constrain'd by that, which forms in you

The reasoning mind uninfluenc'd of the stars.

If then the present race of mankind err,

Seek in yourselves the cause, and find it there.

Herein thou shalt confess me no false spy.

"Forth from his plastic hand, who charm'd beholds

Her image ere she yet exist, the soul

Comes like a babe, that wantons sportively

Weeping and laughing in its wayward moods,

As artless and as ignorant of aught,

Save that her Maker being one who dwells

With gladness ever, willingly she turns

To whate'er yields her joy. Of some slight good

The flavour soon she tastes; and, snar'd by that,

With fondness she pursues it, if no guide

Recall, no rein direct her wand'ring course.

Hence it behov'd, the law should be a curb;

A sovereign hence behov'd, whose piercing view

Might mark at least the fortress and main tower

Of the true city. Laws indeed there are:

But who is he observes them? None; not he,

Who goes before, the shepherd of the flock,

Who chews the cud but doth not cleave the hoof.

Therefore the multitude, who see their guide

Strike at the very good they covet most,

Feed there and look no further. Thus the cause

Is not corrupted nature in yourselves,

But ill-conducting, that hath turn'd the world

To evil. Rome, that turn'd it unto good,

Was wont to boast two suns, whose several beams

Cast light on either way, the world's and God's.

One since hath quench'd the other; and the sword

Is grafted on the crook; and so conjoin'd

Each must perforce decline to worse, unaw'd

By fear of other. If thou doubt me, mark

The blade: each herb is judg'd of by its seed.

That land, through which Adice and the Po

Their waters roll, was once the residence

Of courtesy and velour, ere the day,

That frown'd on Frederick; now secure may pass

Those limits, whosoe'er hath left, for shame,

To talk with good men, or come near their haunts.

Three aged ones are still found there, in whom

The old time chides the new: these deem it long

Ere God restore them to a better world:

The good Gherardo, of Palazzo he

Conrad, and Guido of Castello, nam'd

In Gallic phrase more fitly the plain Lombard.

On this at last conclude. The church of Rome,

Mixing two governments that ill assort,

Hath miss'd her footing, fall'n into the mire,

And there herself and burden much defil'd."

"O Marco!" I replied, shine arguments

Convince me: and the cause I now discern

Why of the heritage no portion came

To Levi's offspring. But resolve me this

Who that Gherardo is, that as thou sayst

Is left a sample of the perish'd race,

And for rebuke to this untoward age?"

"Either thy words," said he, "deceive; or else

Are meant to try me; that thou, speaking Tuscan,

Appear'st not to have heard of good Gherado;

The sole addition that, by which I know him;

Unless I borrow'd from his daughter Gaia

Another name to grace him. God be with you.

I bear you company no more. Behold

The dawn with white ray glimm'ring through the mist.

I must away--the angel comes--ere he

Appear." He said, and would not hear me more.

CANTO XVII

Call to remembrance, reader, if thou e'er

Hast, on a mountain top, been ta'en by cloud,

Through which thou saw'st no better, than the mole

Doth through opacous membrane; then, whene'er

The wat'ry vapours dense began to melt

Into thin air, how faintly the sun's sphere

Seem'd wading through them; so thy nimble thought

May image, how at first I re-beheld

The sun, that bedward now his couch o'erhung.

Thus with my leader's feet still equaling pace

From forth that cloud I came, when now expir'd

The parting beams from off the nether shores.

O quick and forgetive power! that sometimes dost

So rob us of ourselves, we take no mark

Though round about us thousand trumpets clang!

What moves thee, if the senses stir not? Light

Kindled in heav'n, spontaneous, self-inform'd,

Or likelier gliding down with swift illapse

By will divine. Portray'd before me came

The traces of her dire impiety,

Whose form was chang'd into the bird, that most

Delights itself in song: and here my mind

Was inwardly so wrapt, it gave no place

To aught that ask'd admittance from without.

Next shower'd into my fantasy a shape

As of one crucified, whose visage spake

Fell rancour, malice deep, wherein he died;

And round him Ahasuerus the great king,

Esther his bride, and Mordecai the just,

Blameless in word and deed. As of itself

That unsubstantial coinage of the brain

Burst, like a bubble, Which the water fails

That fed it; in my vision straight uprose

A damsel weeping loud, and cried, "O queen!

O mother! wherefore has intemperate ire

Driv'n thee to loath thy being? Not to lose

Lavinia, desp'rate thou hast slain thyself.

Now hast thou lost me. I am she, whose tears

Mourn, ere I fall, a mother's timeless end."

E'en as a sleep breaks off, if suddenly

New radiance strike upon the closed lids,

The broken slumber quivering ere it dies;

Thus from before me sunk that imagery

Vanishing, soon as on my face there struck

The light, outshining far our earthly beam.

As round I turn'd me to survey what place

I had arriv'd at, "Here ye mount," exclaim'd

A voice, that other purpose left me none,

Save will so eager to behold who spake,

I could not choose but gaze. As 'fore the sun,

That weighs our vision down, and veils his form

In light transcendent, thus my virtue fail'd

Unequal. "This is Spirit from above,

Who marshals us our upward way, unsought;

And in his own light shrouds him. As a man

Doth for himself, so now is done for us.

For whoso waits imploring, yet sees need

Of his prompt aidance, sets himself prepar'd

For blunt denial, ere the suit be made.

Refuse we not to lend a ready foot

At such inviting: haste we to ascend,

Before it darken: for we may not then,

Till morn again return." So spake my guide;

And to one ladder both address'd our steps;

And the first stair approaching, I perceiv'd

Near me as 'twere the waving of a wing,

That fann'd my face and whisper'd: "Blessed they

The peacemakers: they know not evil wrath."

Now to such height above our heads were rais'd

The last beams, follow'd close by hooded night,

That many a star on all sides through the gloom

Shone out. "Why partest from me, O my strength?"

So with myself I commun'd; for I felt

My o'ertoil'd sinews slacken. We had reach'd

The summit, and were fix'd like to a bark

Arriv'd at land. And waiting a short space,

If aught should meet mine ear in that new round,

Then to my guide I turn'd, and said: "Lov'd sire!

Declare what guilt is on this circle purg'd.

If our feet rest, no need thy speech should pause."

He thus to me: "The love of good, whate'er

Wanted of just proportion, here fulfils.

Here plies afresh the oar, that loiter'd ill.

But that thou mayst yet clearlier understand,

Give ear unto my words, and thou shalt cull

Some fruit may please thee well, from this delay.

"Creator, nor created being, ne'er,

My son," he thus began, "was without love,

Or natural, or the free spirit's growth.

Thou hast not that to learn. The natural still

Is without error; but the other swerves,

If on ill object bent, or through excess

Of vigour, or defect. While e'er it seeks

The primal blessings, or with measure due

Th' inferior, no delight, that flows from it,

Partakes of ill. But let it warp to evil,

Or with more ardour than behooves, or less.

Pursue the good, the thing created then

Works 'gainst its Maker. Hence thou must infer

That love is germin of each virtue in ye,

And of each act no less, that merits pain.

Now since it may not be, but love intend

The welfare mainly of the thing it loves,

All from self-hatred are secure; and since

No being can be thought t' exist apart

And independent of the first, a bar

Of equal force restrains from hating that.

"Grant the distinction just; and it remains

The' evil must be another's, which is lov'd.

Three ways such love is gender'd in your clay.

There is who hopes (his neighbour's worth deprest,)

Preeminence himself, and coverts hence

For his own greatness that another fall.

There is who so much fears the loss of power,

Fame, favour, glory (should his fellow mount

Above him), and so sickens at the thought,

He loves their opposite: and there is he,

Whom wrong or insult seems to gall and shame

That he doth thirst for vengeance, and such needs

Must doat on other's evil. Here beneath

This threefold love is mourn'd. Of th' other sort

Be now instructed, that which follows good

But with disorder'd and irregular course.

"All indistinctly apprehend a bliss

On which the soul may rest, the hearts of all

Yearn after it, and to that wished bourn

All therefore strive to tend. If ye behold

Or seek it with a love remiss and lax,

This cornice after just repenting lays

Its penal torment on ye. Other good

There is, where man finds not his happiness:

It is not true fruition, not that blest

Essence, of every good the branch and root.

The love too lavishly bestow'd on this,

Along three circles over us, is mourn'd.

Account of that division tripartite

Expect not, fitter for thine own research."

CANTO XVIII

The teacher ended, and his high discourse

Concluding, earnest in my looks inquir'd

If I appear'd content; and I, whom still

Unsated thirst to hear him urg'd, was mute,

Mute outwardly, yet inwardly I said:

"Perchance my too much questioning offends."

But he, true father, mark'd the secret wish

By diffidence restrain'd, and speaking, gave

Me boldness thus to speak: "Master, my Sight

Gathers so lively virtue from thy beams,

That all, thy words convey, distinct is seen.

Wherefore I pray thee, father, whom this heart

Holds dearest! thou wouldst deign by proof t' unfold

That love, from which as from their source thou bring'st

All good deeds and their opposite." He then:

"To what I now disclose be thy clear ken

Directed, and thou plainly shalt behold

How much those blind have err'd, who make themselves

The guides of men. The soul, created apt

To love, moves versatile which way soe'er

Aught pleasing prompts her, soon as she is wak'd

By pleasure into act. Of substance true

Your apprehension forms its counterfeit,

And in you the ideal shape presenting

Attracts the soul's regard. If she, thus drawn,

incline toward it, love is that inclining,

And a new nature knit by pleasure in ye.

Then as the fire points up, and mounting seeks

His birth-place and his lasting seat, e'en thus

Enters the captive soul into desire,

Which is a spiritual motion, that ne'er rests

Before enjoyment of the thing it loves.

Enough to show thee, how the truth from those

Is hidden, who aver all love a thing

Praise-worthy in itself: although perhaps

Its substance seem still good. Yet if the wax

Be good, it follows not th' impression must."

"What love is," I return'd, "thy words, O guide!

And my own docile mind, reveal. Yet thence

New doubts have sprung. For from without if love

Be offer'd to us, and the spirit knows

No other footing, tend she right or wrong,

Is no desert of hers." He answering thus:

"What reason here discovers I have power

To show thee: that which lies beyond, expect

From Beatrice, faith not reason's task.

Spirit, substantial form, with matter join'd

Not in confusion mix'd, hath in itself

Specific virtue of that union born,

Which is not felt except it work, nor prov'd

But through effect, as vegetable life

By the green leaf. From whence his intellect

Deduced its primal notices of things,

Man therefore knows not, or his appetites

Their first affections; such in you, as zeal

In bees to gather honey; at the first,

Volition, meriting nor blame nor praise.

But o'er each lower faculty supreme,

That as she list are summon'd to her bar,

Ye have that virtue in you, whose just voice

Uttereth counsel, and whose word should keep

The threshold of assent. Here is the source,

Whence cause of merit in you is deriv'd,

E'en as the affections good or ill she takes,

Or severs, winnow'd as the chaff. Those men

Who reas'ning went to depth profoundest, mark'd

That innate freedom, and were thence induc'd

To leave their moral teaching to the world.

Grant then, that from necessity arise

All love that glows within you; to dismiss

Or harbour it, the pow'r is in yourselves.

Remember, Beatrice, in her style,

Denominates free choice by eminence

The noble virtue, if in talk with thee

She touch upon that theme." The moon, well nigh

To midnight hour belated, made the stars

Appear to wink and fade; and her broad disk

Seem'd like a crag on fire, as up the vault

That course she journey'd, which the sun then warms,

When they of Rome behold him at his set.

Betwixt Sardinia and the Corsic isle.

And now the weight, that hung upon my thought,

Was lighten'd by the aid of that clear spirit,

Who raiseth Andes above Mantua's name.

I therefore, when my questions had obtain'd

Solution plain and ample, stood as one

Musing in dreary slumber; but not long

Slumber'd; for suddenly a multitude,

The steep already turning, from behind,

Rush'd on. With fury and like random rout,

As echoing on their shores at midnight heard

Ismenus and Asopus, for his Thebes

If Bacchus' help were needed; so came these

Tumultuous, curving each his rapid step,

By eagerness impell'd of holy love.

Soon they o'ertook us; with such swiftness mov'd

The mighty crowd. Two spirits at their head

Cried weeping; "Blessed Mary sought with haste

The hilly region. Caesar to subdue

Ilerda, darted in Marseilles his sting,

And flew to Spain."--"Oh tarry not: away;"

The others shouted; "let not time be lost

Through slackness of affection. Hearty zeal

To serve reanimates celestial grace."

"O ye, in whom intenser fervency

Haply supplies, where lukewarm erst ye fail'd,

Slow or neglectful, to absolve your part

Of good and virtuous, this man, who yet lives,

(Credit my tale, though strange) desires t' ascend,

So morning rise to light us. Therefore say

Which hand leads nearest to the rifted rock?"

So spake my guide, to whom a shade return'd:

"Come after us, and thou shalt find the cleft.

We may not linger: such resistless will

Speeds our unwearied course. Vouchsafe us then

Thy pardon, if our duty seem to thee

Discourteous rudeness. In Verona I

Was abbot of San Zeno, when the hand

Of Barbarossa grasp'd Imperial sway,

That name, ne'er utter'd without tears in Milan.

And there is he, hath one foot in his grave,

Who for that monastery ere long shall weep,

Ruing his power misus'd: for that his son,

Of body ill compact, and worse in mind,

And born in evil, he hath set in place

Of its true pastor." Whether more he spake,

Or here was mute, I know not: he had sped

E'en now so far beyond us. Yet thus much

I heard, and in rememb'rance treasur'd it.

He then, who never fail'd me at my need,

Cried, "Hither turn. Lo! two with sharp remorse

Chiding their sin!" In rear of all the troop

These shouted: "First they died, to whom the sea

Open'd, or ever Jordan saw his heirs:

And they, who with Aeneas to the end

Endur'd not suffering, for their portion chose

Life without glory." Soon as they had fled

Past reach of sight, new thought within me rose

By others follow'd fast, and each unlike

Its fellow: till led on from thought to thought,

And pleasur'd with the fleeting train, mine eye

Was clos'd, and meditation chang'd to dream.

|